How do you know what you’ve written ‘works’? Or how do you try and entice the most effective choices into your thinking and planning early, to avoid masses of rewriting later? How do you save yourself from getting overwhelmed entirely by the whole act of writing a play, and never finishing (or worse, never starting)?

The best way to start writing a play is to start writing a play. That might sound glib, but I think it’s true.

The next question is probably ‘how?’, to which there are a hundred possible answers. This one is just mine.

I’ve been revisiting this thinking recently, ahead of my Playwriting Intensive online course for Forest Forge Theatre Company: a small writers’ group where participants will share and develop their ideas for one-act plays over four sessions, sketching out their openings and their key ideas so they have a clear springboard to plough forwards into the whole.

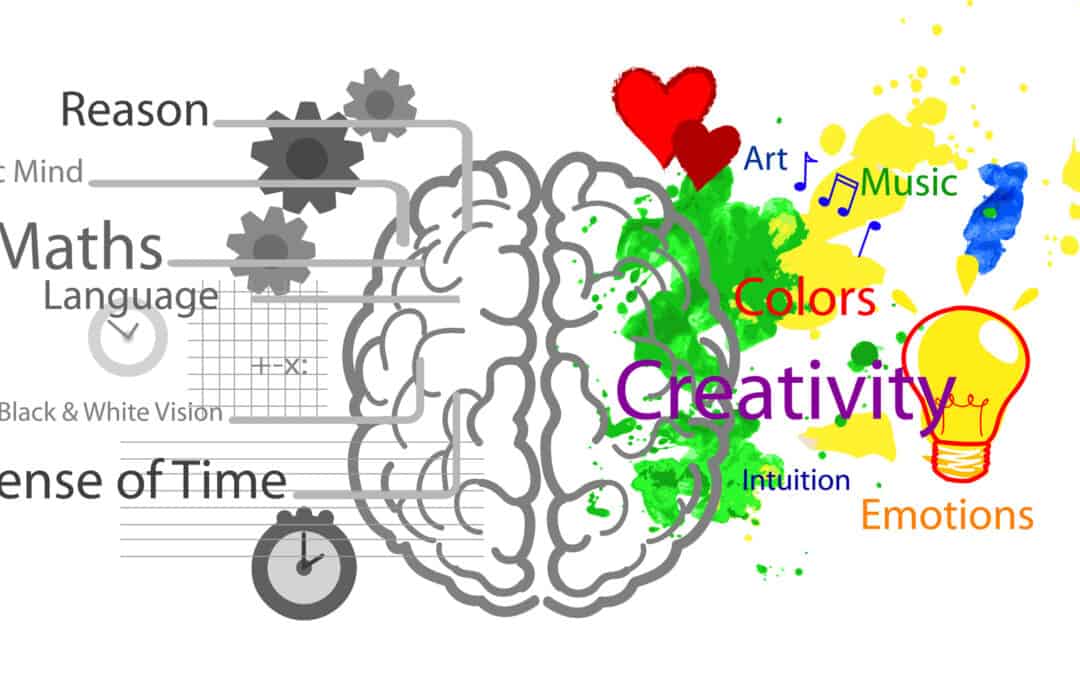

I think every creative process needs two parts of our brain – the free-thinking and the schematic – but in different quantities, at different stages, and differently from project to project.

In a previous blog I was bringing together some thoughts about how our ‘source’ material – our starting points for plays – could benefit from some of the writing strategies we might apply to adaptation.

Much of that was focused on the idea of ‘expressive’ structures – patterns and sequences of action that could express a character’s distinct experience of the world as they perceive it to be.

I favour adaptation practice as a bedfellow to original playwriting practice. This is because it draws on three distinct areas in my own work:

- the analytical, pattern-finding and under-the-bonnet thinking of dramaturgy, which you need if you’re truly going to get to grips with a source text

- the creativity of playful, unexpected, free-thinking innovation in original writing and

- the transformation of research (in all its guises) into dramatic and theatrical forms.

To go deeper still, it also relates to a right brain (creative, spontaneous, free) / left brain (logical, schematic, critical) relationship in playwriting process, that you’ll often find me barking on about if you’ve ever caught me running a workshop because it’s become one of the most useful distinctions in my own practice.

(To be brutally honest, the right brain / left brain distinction has been debunked by many neurologists now as a myth of over-simplification in terms of how the brain works, but I’m going to persist here for entirely selfish reasons…)

Imagine you’ve got a source text to adapt in front of you.

The instinctive right brain will probably be informing your adaptive choices because you’re emotionally fired up in some way – you’re gripped by its existing story, or character, or set of politics, or world: it speaks to you and/or the world around you, provokes you, leaves you reeling with wonder, pulls you in and doesn’t let you go.

When I adapted The Odyssey – my first ever adaptation and my first full-length play – my instinctive pitch to the company at the interview stage was simply that it was connected to war, heroism, the people left behind and the storytelling that wove all of that together (I’d literally only read the Spark Notes and was pretty much winging it). I didn’t know much else, but my instincts told me those were worth pursuing. Very right-brain.

Our reasons for getting switched on by the ‘source material’ we’re adapting – whether that’s an epic Greek poem, a contemporary novel, classic play, fairy tale or something else entirely – can often be wholly instinctive and singular.

We’re emotionally gripped by a moment, an image, a concept, or a character choice, and our instinctive right brains are driving us towards our fascination with that.

And I think the same goes for playwriting when we’re trying to generate original material in response to a stimulus or itch. How often have you (or someone you know) said ‘I’ve got this great idea… but how do I turn it into a play?’.

I think this often happens because we’re being driven by that right brain: that impulsive passionate part of us that is free-wheeling but not yet structured.

Frustratingly, that right-brain is also where we can harbour an unfair expectation of the genius artist model to get to work, where everything kind of magically works itself out when we’re in the moment of writing.

Those moments can happen of course. Every creative journey needs that belief, and probably does contain a moment where the stars somehow align – but I don’t think those moments happen by accident.

I think those creative, inspirational, light-bulb right-brain moments are often (conversely) down to some activities concerning the logical, ordered and structured left brain.

Here’s an example.

I was writing a play based on parkour and free-running a few years ago. At the beginning, I wanted to write a play about parkour because it was exciting and beautiful to watch, had the theme of transformation at its heart, and involved teenagers who are constantly evolving in their vision of and values about the world.

So I’d researched parkour. I’d walked around the Square Mile imagining I was a free runner, taking photographs of potential training routes. I knew I was writing a drama about people searching to better themselves somehow.

I wanted to search for the extremes, the far edges of the material. I’d come to learn loads about it as a discipline and philosophy. I knew that some people felt competition was destroying the sport (that even calling it a sport could be anathema).

When I asked a parkour coach about the ‘peak’ of parkour, her answer suddenly provided me with both the dramatic and theatrical nature of one of my characters in a nutshell.

She described the ‘peak’ being like that moment in The Matrix where Neo sees the world in binary code and can stop bullets, bending time and physics to his will.

‘It’s like you can leave the house one day and run and run forever without stopping: like your body can instinctively read the urban landscape and is inseparable from it.’

Right-brain BOOM – the character of Zara was born. A figure running from a life she had to leave, who was part-architecture, part-human, part-ghost, part-biology, part-steel and stone. I hadn’t any inclination to write anything other than realism up to that point.

It was the birth of the whole play, in truth.

But I think that moment of explosive creativity, triggered by the parkour coach’s comments, came about because of many days of research with intent. That had come from the left brain for sure.

Had I met the parkour coach at the start of my thinking around the play, I’m not convinced I would have understood the significance of the metaphor she placed in my lap, which led inextricably on to a character, a world, a need and a potent poetic theatricality.

The learning? If your free-wheeling right brain isn’t finding the dynamics in your idea to bring it life, you can at least use your left brain to try and create the conditions for inspiration to visit.

That’s not meant to sound mercurial. In fact in practice, I find it’s the opposite – it begins with the logical left brain simply working the raw material of the idea through a simple categorisation exercise.

For example, when I adapt, it starts with finding the dramaturgical categories in the source text that I recognise: characters and their choices and transformations in space over time – hunkering down to the pure dynamics of story so I can fully understand how they work.

This has now been transferred to the way I create my original plays.

But you don’t have a whole text to analyse at the beginning, so instead I do this through a particular process of generating research material – and you’ll all find other ways according to your own tastes and practice – and then creatively working through that material, considering where it connects to various dramaturgical categories.

I’ll search for patterns, sequences, shapes, metaphors, oppositions, meanings, value systems, places, people, rules, objects, sounds and languages that might construct a play’s world. Then I’ll try and explode outwards from these and imagine possibilities in dramatic and theatrical terms.

Left-brain categorisation, but opening up a right-brain creative stream of thought.

I’m rarely thinking in complete story terms or plot terms when I do this – I’m trying to construct the play’s overall universe. A play’s universe is the only world in which its characters exist. It is not our world. It is the world from which crucial plot ingredients of pressure, context, urgency and deadline arise.

The story world is your characters’ only home. They are sprung from it, moulded by it, and respond in relation to how they see it and what they understand their place within it to be.

If you’ve created that entire universe and all its elements by riffing around what’s at the very core of your idea (I riff on that core through research: others among you will do other things) then I think you’re much more likely to discover the dramaturgical choices that can express your characters’ experience of it.

Characters are motivated to make choices in response to ruptures and imbalance in their internal and/or external environments.

More often than not, it’s actually a discord between their internal environment (how they see themselves and their abilities to survive in the world) and external environment (perceiving that the world doesn’t fit them properly, so they can either change it, or change themselves).

At an extreme theatrical level, as with Anthony Neilson’s The Wonderful World of Dissocia, we spend the first act of the play entirely within the character’s internal environment, and spend the second act of the play entirely within the character’s external environment.

The contrast between the two is what suggests the complication and tragedy of the central character’s experience of the world. It expresses the dramatic problem at the heart of the play with a striking (though deceptive) simplicity.

I started out by talking about adaptation. As an adaptor, you’re in charge of deciphering that universe that’s been created by somebody else and understanding how it works: as a playwright, you’re in charge of creating that whole universe yourself, and understanding how it works. But you need to be both physicist and artist, scientist and mad genius, left brain and right brain.

The human experience of our world isn’t reducible to schematics alone – it is mercurial, and mysterious, and wonderful and slippery. The process of writing a play is (and I’d argue should be) all of these things as well.

But if we can consciously guide that process towards the deeper, unconscious inspirations, coaching ourselves to sniff out the most effective choices, the worlds we create will be even stronger at expressing those unique experiences of our characters.

Enjoy this blog? You can get more insights and receive weekly updates on competitions, awards, submission opportunities, jobs, training and workshops by signing up to Lane’s List – every Wednesday, 50 weeks a year, to your inbox.