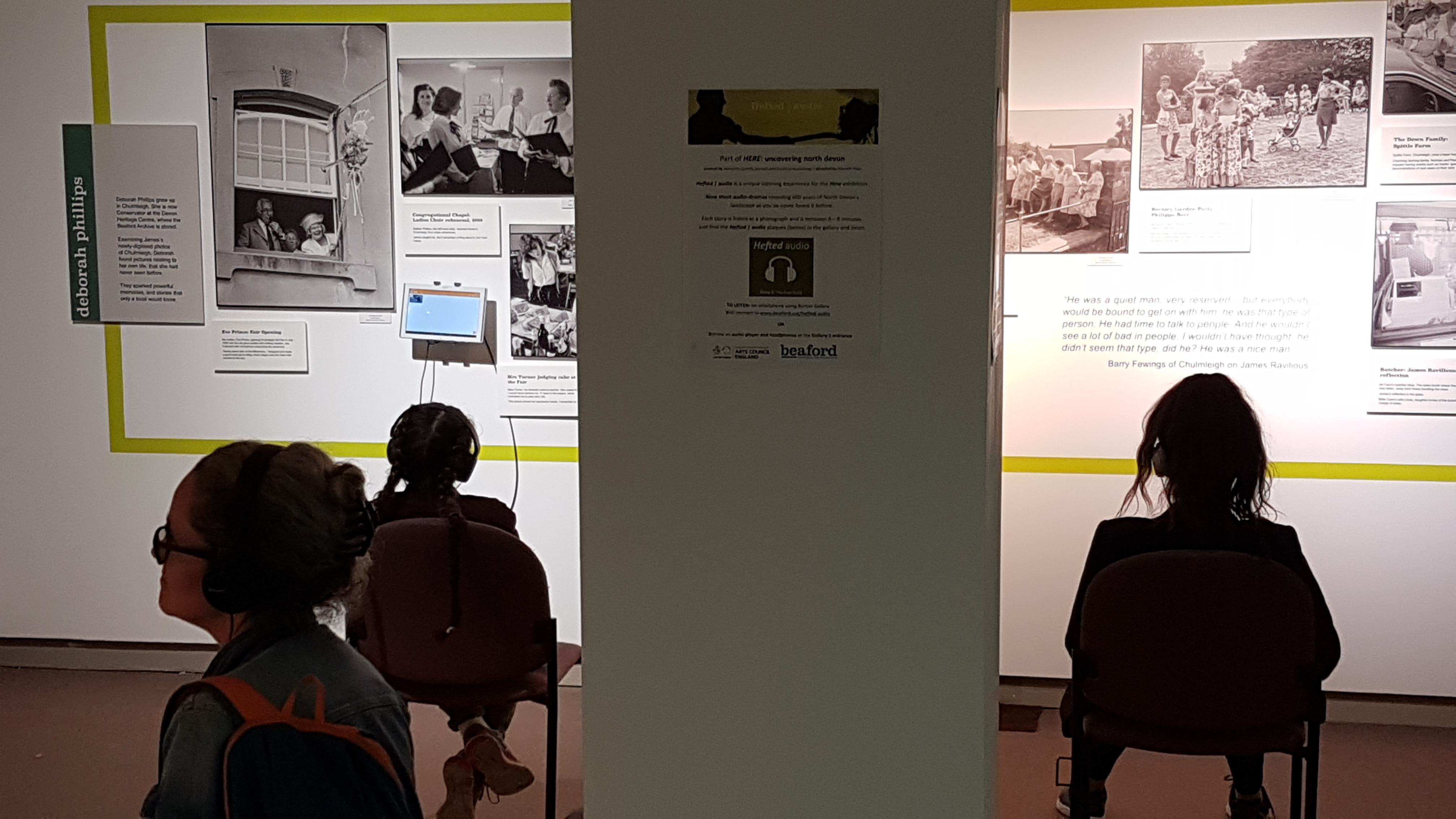

(Listeners at Hefted | Audio‘s launch at the Burton Gallery, Bideford – June 2019)

This year I took on writing for audio for the first time, supported by Arts Council England to work with sound designer Adrienne Quartly and adapt my North Devon-inspired stage play Hefted for online listening.

This is the second in a series of six blogs reflecting on what I learned.

I was completely new to the art of writing for audio at the beginning of this project. The most I’d managed to muster was a five-minute drama for a BBC Radio Five Live competition in my early twenties, and then more recently (well, eight years ago) the first ten minutes of a potential radio play created via an incredibly good workshop with BBC writer/producer Sara Davies in Bristol.

It was Sara to whom I immediately turned so that I could budget her into my ACE application as an audio writing mentor. The application was being part-driven (and by that I mean part-funded) to support my artistic development, so mentors are generally seen as A Good Thing by ACE as an assurance of quality control.

In my previous blog I outlined how Hefted was originally conceived to support multiple mediums without too much transition. I was feeling pretty confident about transposing it to audio.

One of the things I’d woven into the stage version was a distinct sound landscape – a series of indicative soundscapes, noises and other audio motifs – which acted as a sort of glue through the 600 years of the play and were also evocative of the multiple North Devon locations in the piece.

In addition, there were several scenes which were more like monologue or direct address, which I felt could translate well to audio without very much adaptation at all. There were also a couple of choric or group scenes, where storytelling was shared out between voices.

I was seriously confident that this would all be ready within a couple of drafts. Adrienne would add the necessary sound effects as they were in the script, and we’d pretty much be there three months.

I was about to go on a very steep learning curve indeed.

For my first meeting with Sara Davies I’d asked her to read the theatre version of the script, and give me a sort of Writing for Audio 101 in relation to what was there on the page. Where were the possibilities? Where were the big challenges? Again, I was feeling pretty confident in the material at this stage.

Sara was brilliant and very direct. She covered basic dynamics of the act of listening which would inform my adaptation choices in ways I hadn’t even considered.

With the stage, people commit to a length of time and a place. They’ll sit down and have a beer and a chat with a friend and the lights will go out, and then unless it’s completely awful you know they’re going to stay there, and their attention is pretty much focused entirely on what is in front of them – an act which is assured in part by the nature of collective spectating.

(The original cast with script development director Ed Viney, July 2018)

People will listen to audio alone, and in all sorts of different ways. They almost certainly won’t listen to it in one go. They’ll be on the way to work, or doing something else, the washing up, on the bus, dipping in and out whenever’s convenient for them and – as a result – skipping over or checking out from anything that doesn’t win their attention. It’s not a sealed contract. You can’t guarantee they’ll be with you all the way.

With audio, you’re in competition with the rest of whatever is in that person’s field of vision which is ABSOLUTELY NOTHING TO DO WITH YOUR PLAY.

I didn’t realise this at the time, but the answer to that maintenance of attention was an incredibly condensed text (in comparison to the stage version) and a striking atmosphere, which was about emotional mood, which was about dynamic, which was about Adrienne having space to work and think and respond creatively.

Sara also talked about the power of the human voice to communicate meaning and story. I heard this, but I didn’t register what she meant. I thought she just meant really good acting. She didn’t.

Four months later in the studio when I saw our director Hannah Price doing take after take after take, straining her ears into her headphones with her eyes closed like some kind of zen audio wizard whilst both a sound designer and studio engineer listened along just as intently, I realised what she meant.

With audio made specifically for headphones, through recording microphones worth around £1500, you pick up the performer’s every breath, inflection, hesitation, wobble, bump and waver. Florid and poetic language becomes useless.

The dexterity of a well-trained voice is the instrument of focus.

There were practical limitations as well. We had limited tech in the studio, no foley artist, no opportunity to record on location (we had the actors locked into specific days and times and studio booking slots).

We had a very small booth studio without a 100% guaranteed dead space, which made any scenes which were outside, or with fighting or extensive movement (of which there were a few) nigh on impossible to do effectively. They’d have to be re-conceived.

Recreating reality is the hardest thing to do in the studio. Sara pushed Adrienne and I to think much more about tone, world, quality, metaphor, poetic sensibilities – not, as I’d originally thought, just transplanting scenarios from stage to audio.

On stage we fill in the gaps and suspend our disbelief. A stage block can be a hillside or a train station platform or a rock on a beach – but when it’s only your ears being fed, you have to get it right because your brain is trying to build a picture of reality.

Don’t make it real, was the advice. We had neither the tech nor the team nor the time to achieve naturalism to that level. Let audiences arrive at the picture through a much more metaphorical and much more theatrical (ironically) pathway.

This audio adaptation thing was more complicated than I’d anticipated.

I studiously went away and, via a first feedback meeting with sound designer Adrienne – which I’ll talk about in the next blog, looking more closely at the writer/sound designer collaboration – I got a draft prepared which I felt had responded really well to these notes.

I think the polite phrase is that it got slammed.

I am being colloquial here – Sara was a total professional about it! But it wasn’t good enough. There was literally no space for Adrienne to create anything original (unsurprisingly she wasn’t that interested in just going through a library of sound effects to follow my theatre script’s naturalistic weather soundtrack) and the script still needed cutting by around a third before we even thought about going into a studio.

It had been a long, long time since I’d felt like a total novice at anything to do with dramatic writing.

It was a very odd and in retrospect, incredibly useful feeling. I couldn’t just rely on the stage version mimicking what I’d done before and then recording it in a studio. A few edits and interior voices here and there wasn’t going to cut it. This was about wholesale conceptual change.

I was having something that had been incredibly successful in two other versions being undone and rightfully criticised – I realised I had to go much further back, un-thinking my way out of the stage conception seared into my brain and building again from the dramaturgical beginnings: the emotional heart, the dramatic impulse, the character stories – get back to basics, and then in collaboration with Adrienne, use our joint understanding to use only what was definitely still needed from the original words, and ditch the rest.

The uniqueness of the audio medium was coming over the horizon at a rate of knots and I had to respond to it by learning very quickly and re-thinking the script scene-by-scene.

Some of my favoured pearls of wisdom for writers new to theatre were now being doubled back at me.

Firstly, with adaptation, know your source material well enough to dissect it and understand it from the bottom up, so that you can intervene creatively with it. Transposition of medium is not enough.

Secondly, you learn best through seeing work in production – watching it being worked on and then received by an audience, and then watching it again, and again.

This couldn’t happen until we were in the recording studio itself: although since that point, listening to it again and again and having different people listen to it in different contexts and feedback their thoughts, I feel like I could write for audio so much more effectively now. I understand the potential of the medium and how to work with it so much better having watched the process from beginning to end.

Thirdly, you have to fail. When you’re learning you have to make big mistakes and sometimes face big lessons. Seventeen years into writing for theatre, this happens far less often.

A month into writing for audio, it was raw and tough and a shock to the system. It was a wake-up call to better respect the medium – the distinctive demands of a nine-part sound and audio composition with words, designed for headphone listening.

That shift in vocabulary was useful.

You say ‘radio play’ and it comes with associations. You say ‘sound and audio composition with words, designed for headphone listening’ and the complexities go beyond people stood around a microphone saying words with a good sound effects track in the background – yes, that was my naïve understanding, now helpfully blown to smithereens!

(Gill Nathanson and Bill Buffery in rehearsal)

The draft really began to find its gear once Adrienne and I began to collaborate more closely as a writer/sound designer partnership.

Once we understood the limitations of our studio and time, once we understood the world of audio drama and what was possible, once we knew we wanted to sit somewhere between BBC radio play and sound art, it became easier to make decisions, to try things out, to even carve out time to experiment in a schedule that needed about 50% more creative time and space (my bad – another blog on what I learned through self-producing to come!).

This blog is about one realisation – making space in the text-led storytelling to respect sound.

This means respecting the impact of anything that isn’t the words themselves. The way they’re performed in that incredibly intimate studio set-up; the scaffolding and architecture of the sonic world; the effect of original composition, of emotional atmosphere and dramatic mood, and how silence acquires huge power when used within it.

As soon as I allowed the text to make space, the rest of the creative team had space to create too: and that’s when the adaptation to audio genuinely began to take shape – when the text had respected the space for their vital artistic contributions to the whole.