This blog was originally published in Summer 2016.

Today my evaluation is submitted to Arts Council England for my ACE / Peggy Ramsay Foundation-funded Protected Time to Write project. This is the final blog in the series of 10 tracking a playwright’s process from initial ideas to first draft, in a bid to share some of the learning that’s come out of it.

‘What are you going to do differently this time?’

Jonathan Lloyd, Artistic Director of Pegasus Theatre and my mentor on a new research and development project adapting George Orwell’s Animal Farm – which is designed for classrooms, with the performance exploding unexpectedly into a school day and inciting student revolution (hopefully) – has read Blog 9 on failure and process from this project.

‘It’s such an honest and intriguing set of realisations – so what’s stopping you from just sitting down soon and writing a quick draft?’

This is my first meeting with him as a Leverhulme Scholar under the egg Theatre Royal Bath’s established Incubator scheme, which sees artists developing new work for young people – everything from early years to older teenagers – and then sharing it as work-in-progress excerpts in September in front of an industry audience.

I remember being at exactly this stage with the ACE project.

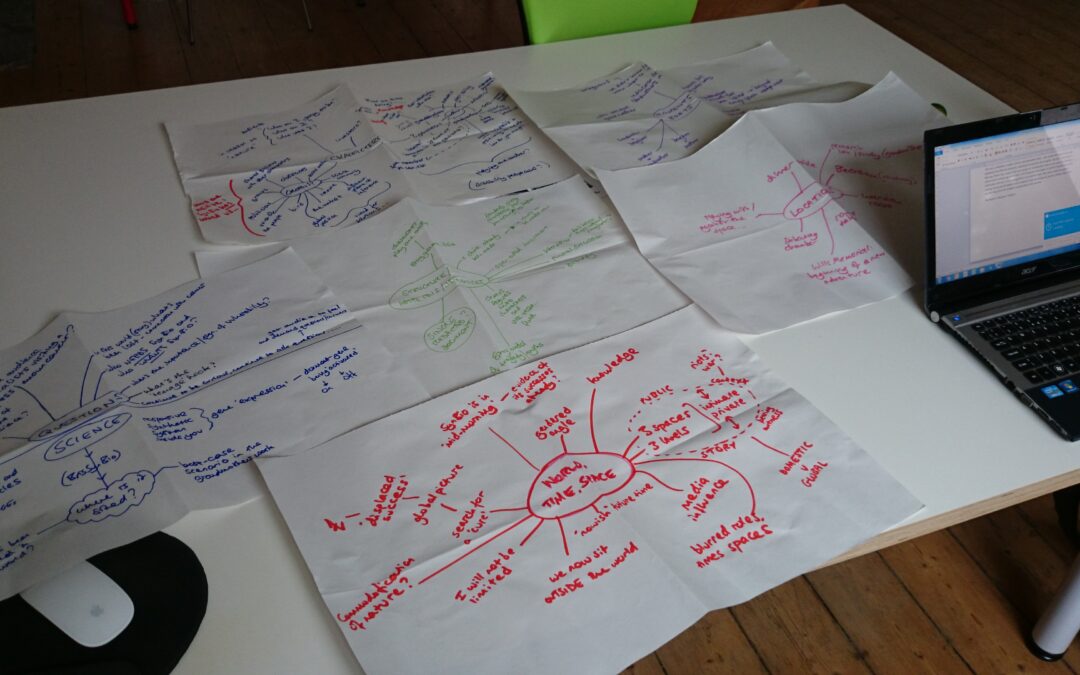

There was lots of research under my belt, creative practical meetings and conversations with other artists done, piles of research and scrawled thoughts, questions and mappings all around me – though this time I’ve done them willingly, not because I felt I had to do them – and then facing my dramaturg for the first time, wide-eyed and excited by the enormity of the idea but relishing its artistic possibilities.

The difference this time was that I sat there and stated what I wanted the play to look like.

I put down my non-negotiables that were coming from my instincts and passions. I told him what the form, world and intentions were. I didn’t shirk from stating ambitions that, two years ago, I would have balked at as being too difficult or grandiose – and too similar to some of my previous work in concept.

Artistically, I want to make the most effective choices. If that means the play becomes too complicated, risky or pragmatically unwieldy to tour into schools, that’s fine. The work will have artistic integrity and I’ll try and find where it does sit.

All of this is happening because I feel more empowered in my voice, my process and the truth of my ideas – why they make me passionate, what I want to shout about, what’s fuelling the endeavour. That’s as a result of a project where I allowed these things to burn out in favour of second-guessing that imagined industry who’d receive the piece, desperate to please. Now, I feel a little bit anarchic.

I say anarchic because for me, it’s tied up with a pressure I’m now questioning – one that derailed me before – of writers only being able to make themselves visible within the industry and ‘marketplace’ by clarifying their ‘voice’ in script form.

One of the driving factors of applying to do this original project was identifying my singular ‘voice’ as a playwright.

The assumption I (wrongly) made from the swirl of noise around me when I applied for funding was that my writing voice was absent, wasn’t formed yet, and wasn’t consistent – was not singular – and I turned this into my main concern about my writing: that all my plays sounded totally different. By writing a play that pinned it down securely for now and time immemorial, I would write (and continue to write) things that automatically leapt out to literary managers.

Having been in that situation on the other side of the desk as a script reader, I’m not saying that voices don’t leap out – I read Jack Thorne’s first play in 2003 and it did just that – more that the necessity to have one perhaps comes from a now outdated singular career pathway for playwrights, based on the unsolicited manuscript submission route. Send play in, get ‘voice’ noticed among the thousands, build relationship, get commission, have play put on. Repeat.

I’m not bashing unsolicited pathways. They’re imperfect in design but also vital. They democratise the way in and allow unheard voices to be heard.

I’ve also worked bloody hard to get to a position professionally where I don’t need to rely on them – but despite that career experience, it still didn’t stop me having a deep desire to please the ‘gateholders’ with a certain sort of voice, and that desire then f***ing up my attempt to write a play that was truthful to me.

However, I also think it’s a career model better supported by the incredibly well-funded new writing sector from the beginning of this century; fifteen years later, the unsolicited or competition route co-exists alongside self-starting, self-funding, short play scratch-sharing relationship-building models where writers find themselves (for economics as well as artistic desire) collaborating from early stages with others. My weekly mailing list is a case in point this week: there are several workshops and articles about self-producing, pitching, managing your career progression, and thinking with a business head on about your industry.

Personally, of the seven projects I’m currently engaged with as writer, every single one has come out of a conversation or pre-existing relationship, not an unsolicited script route.

These projects move slowly – we are talking three or four years from initiation to desired production date. They are funded in stages. I’ve co-written write the funding bids for a third of them, and through that collaboratively define and re-define the intention, artistic drive and necessity of the piece. My voice alongside the voices of the other artists involved shifts across them like a chameleon, my skills manoeuvring to best serve each individual project. Without question the work is getting stronger as a result.

What is ludicrous is that I thought two years ago that this meant I wasn’t a proper playwright. I wasn’t in a room on my own with scripts falling out from beneath my fingertips that engaged with the political world in ardent, ferociously angry ways, and therefore the only way to develop further in my career was to make myself do that. Now I know that’s a load of crap.

I can only speak from my own position. I was lucky enough to start my career in those better-funded times. But even my first commission in 2006 didn’t come from an unsolicited script – it came from applying to an open workshop recruitment evening at Half Moon Theatre three years previously.

Aged 23 I got invited to share a three-minute writing exercise alongside twenty other freelancers in a two-hour recruitment session. They asked me to come on board, and over the next two years I was assisting, facilitating and then designing and writing short-term project-based scripts for young people of 15 or 30 minutes.

Then I got the confidence through building that relationship with the company to ask for a shot at something more substantial and tentatively road-tested some ideas collaboratively with schools. The professional commission for a touring play for teenagers arrived about three years after that very first open workshop. This year – a decade later – I’m working on my third play for them.

Just to mention at this point – these ten blog posts have not been rule-books for playwriting: they’re just reflections of something one person did and felt. My learning won’t apply to everyone.

But the example above is why I am absolutely committed to promoting to writers the importance of finding the places where you can practically operate as a writer. It’s why I always promote workshop or facilitation roles on my weekly Lane’s List mail-out, not just places you can send scripts to. It might be in a theatre venue or in a scout hut, a school, a community centre, a hospital, a park – but once you’ve put yourself in a position where you’re seen as a writer, you never know where it might lead.

My relationship with Half Moon began with being a workshop assistant, but it was somewhere I felt I could call myself a writer. And feeling that gave me the confidence to grow and introduce myself to other people as such – it wasn’t about having a voice, but about carving out a space where I could have an identity as a writer in a practical way.

My search for ‘voice’ was the seed of the entire ACE Protected Time to Write project. I thought it meant something stylistic, ‘sounding’ a certain way on the page – then I thought it was about content, replicating the sorts of plays that were out there on the ‘big stages’. Now it all feels more subtle than that.

I think your voice is your set of values as a human being: your philosophy, your mythology about the way the world works that you’re continually wrestling to identify. I have thought this before, but back then I clearly didn’t believe it, or I would have turned round to my process and told it to piss off and then written what I actually believed in.

Some of what comprises that mythology (yes, yes, I know I’ve stolen the phrase from Simon Stephens but who better to steal from) will of course change through your life, just as the world changes. Becoming a Dad certainly did that for me.

But some of it will doggedly stay the same. And from project to project as a playwright, you’re calling on the different facets that form that voice to serve the particular purpose of the story you’re telling, and the experience you want to communicate.

I love the surprises and new challenges that come with that. I don’t want everything I write to ‘sound’ the same. From a business point of view, that flexibility is marketable. I’m not sure for me that a singular voice is.

I’m also not saying that I’m ‘voiceless’ or that I’m utterly different with every single play I write. I know I write poetically, that I’m interested in the extremes of the everyday, that I’m obsessed with stories about stories, that language is the muscle I’ll always try and work hardest in a play, that I’m pulled in by imaginative structures for storytelling, that I want my stories to transcend reality and occupy metaphorical worlds, be beautiful and lyrical, that I respond better to being given a brief and bashing around ideas than self-generating entire worlds and stories, and that I love the old-school people-in-a-shared-space-acting-a-play theatricality.

It’s just that I’m not going to worry anymore about whether that’s what I should be excited by. I’m just going to get on with writing the plays.

So when I was asked:

‘What are you going to do differently this time?’

– I knew that the answer was to just do some writing: not to worry about being a certain kind of writer. I had that journey. Now it’s time to take a new one.

Hope you’ve enjoyed all the blogs.

Project closed.