The first fortnight from seven weeks – and my first dramaturgy meeting – has now elapsed in my Arts Council and Peggy Ramsay Foundation-funded Protected Time to Write project. This is the third blog in a series of ten tracking a playwright’s process from initial ideas to first draft, in a bid to share some of the learning that’s coming out of it.

You can read Blog 1 here and Blog 2 here.

Blog 3 first appeared in Lane’s List on April 6th 2015.

Child Bereavement. 100 Days of the Syrian Revolution. Vogue on Arabic Modern Art. Embedded Journalists on Video and in Writing. Press Photographs. A History of the Division of the Arab States. Radio 4’s Archive of From Our Own Correspondent. Al-Jazeera. ABC News. Woman’s Hour. Syrian State Broadcasters. UN Reports. The Refugee Council. Syrian Contemporary Art in a Time of Revolution. Two 30-Minute Interviews with President Al-Assad. Chemical Warfare on the World Service: A Phone Discussion. Pamphlets on Grief. Mini Documentaries by Citizen Journalists on the Syrian Frontline. Protest Footage. Academic Talks on the Female in War.

That’s not the end of the list. It comprises about three-quarters of the resources I’ve been engaged with over the last ten days, across books, YouTube, magazines, interviews, films, radio and documentary. But last week I officially called time on initial research, and went for my first dramaturgy meeting in a bid to find that crucial outside eye on my work.

It was my first official dramaturgy meeting: I feel more like I’ve had five already, thanks to the suggestion to include impromptu coffee meetings with other theatre-makers at random points through the last fortnight, with little agenda my end other than asking for permission to talk and see where it led me.

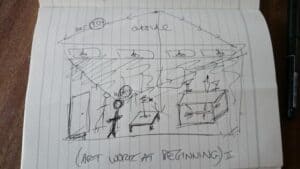

An actress, an actor-director, a live artist and an artist development producer have all played their part in giving me dramaturgical space – space away from the idea to think and question, speak it out loud, test it in conversation, and even be challenged to draw how I see it in my head (see above, with thanks to Bryn Holding for pushing me to go there).

However, these all happened in the security of knowledge that I would have a 90-minute dramaturgy meeting to officially seal off my new research archive – at least temporarily – and after two weeks, begin to transpose fact and experience into human story that can speak to an audience.

I’ve always been a responsive writer – research-led, brief-led, immersing myself broadly, reading widely, interviewing, note-taking, YouTube trawling, trying to get as close to the suspected world of my story as I can.

I love this bit of the process. There’s nothing quite like stumbling across that nugget of information which becomes unexpectedly useful – like panning for gold. There are moments when suddenly you feel the dramaturgical synapses independently firing and you connect an image, a word, a phrase, a form, a storyline, a character all together in an instant, grabbing blindly for a pen before it departs your line of vision.

There’s also a lot of wading through the less useful – but I’ve always found that research becomes both the pencil and the sharpener: the more you know, the more you discover what you really need to know, and the more focused everything becomes.

You start to pick up on patterns, motifs, recitatives, habits, rhythms… the world you’re exploring becomes coherent and connected rather than bewildering and alien. That’s when you know the research ascent has plateaued, and it may be time to slow down, look around, take stock. Acknowledge what you know and what’s left for you to make a creative leap of faith.

I thought I’d left myself deliberately open at the start of this writing process. I’ve been making very few choices, resisted tying things down, kept an open mind. My research notes are peppered with creative questions about story and character which I’ve simply posed before moving onto the next source. There’s around seventy I think. Looking back now, they are the next task list for phase two of the writing process – dredging up character and world and lifting them into an independent, interconnected organic story world.

I’d fallen back on some familiar habits too – nothing that hasn’t been practical and helpful – but, in light of that first official dramaturgy meeting, habits that are reintroducing things I’ve always done in my writing because I know that they work.

That was another rule I’d given myself on a project that is 50% about writing a play and 50% about knowing my own process better: not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, but to allow myself the security of what works rather than crippling myself with a completely open space and no scaffold to hang off, no habits to shape my early research.

In the meeting, like all good dramaturgs, mine permitted me time and space to speak first.

Fortunately another friend had suggested I prepare my own agenda: what I wanted to say, what I wanted to know, what I would find helpful, what specific questions I had – all while staying open to being surprised, challenged, shifted in direction and asked as-yet-unanswerable things about my play. This agenda was shared and I began.

I skipped through some of the early big words and themes that occupied the first few days of research (both into myself as writer, and into this idea) – mythology, Syria, meta-stories, women, politics and protest, state and individual, rearranging the cosmos with narrative, poetic sensibility, the grand metaphor – and quickly shuffled on to the much more specific facts and experiences that had characterised my later gatherings.

If you picture an iceberg in the ocean, I started my report back to the dramaturg at the invisible base, before quickly shooting up the top – to show that I really had my head above the water, that this wasn’t about the abstract concepts underpinning an idea, deep down and out of sight, but about the drama and characters and what was going to be clearly visible above the waterline for an audience.

This went on for about forty minutes. It was really useful. What was at the top of my head was what needed to spill out. She waited patiently, scribbling and occasionally probing, until I did one final check back through my notes so far then sat back and listened.

Then – if you’ll allow me to stretch the metaphor – the remainder of the meeting was spent pushing my iceberg up from below: big strong weighty questions that could bear the brunt of an iceberg’s mass, heaving it up from beneath, down where all that foundational stuff was, and shoving it up and up, water sluicing down the outsides until the visible bit of the iceberg – the bit the eye can see, the bit the audience engages with directly – was mammoth. The play became immense in potential.

Think. BIGGER.

Without realising it, I’d made too many choices already. I’d done what I already knew how to do, and am good at: distilled, compressed, packaged and neatly poeticised the research into a little boutique studio play with a stripped-back aesthetic and a punchy muscular language.

That’s not the point of this project, I was helpfully reminded. The point is to stretch beyond, go towards the unknowns, take on the bigger project. Move out of the shallows.

I’d reined in an awful lot. I’d reined in point of view, number of characters, world, the rules of the world. I’d jumped ahead in my planning but somehow subconsciously, and my dramaturg (just as I’d done with my own research) sifted through what I’d said across forty minutes and panned for gold.

She identified the initial excitement, the boldness, the possibility for the ambitious and audacious. Don’t do what you’ve done before, she said. Plunge in. Take the risk. This opportunity might not come again.

It’s difficult (ironically) to distil it into lessons, or even specific questions that could be useful in any other context – but the sentiments I remember now:

Explode the idea back out again – landscapes not rooms

Think operatically – think scope and peaks and troughs of emotion

Think global, think multi-narrative, multi-timeframe, think surprise

Make it more difficult: for yourself, for the audience – don’t over-simplify

Think production: the scale of what’s possible now, think projection, think digital

Be overt, not distilled and quiet: be bold

Stay true to the heart of where you began – don’t underplay the strengths

Be less cautious

Nearly every play I’ve written in the last seven years has had the luxury of a pretty-much confirmed production date at the time of writing. The context has provided it (young company work, community work, short play festivals, small companies with limited commission funds, tight budgets, established relationships of trust). At the very least, the idea has been requested or road-tested, invested in, and has the weight of a company behind it.

It’s just me now. Nobody’s asked for this play or this idea. Public money is being invested in it. I’m so lucky – I’ve worked to earn this investment over the last decade, I know that – but I still feel lucky.

I am panicked and scared and hugely apprehensive and incredibly excited all at once. I sense I can do this but I have no idea if it’ll come out right. I don’t know if it’ll work.

But tens of thousands of writers are doing this all the time across the country. Writing speculatively, having faith, and most of them aren’t even paid. I’d forgotten what that was like. I have so much bloody respect for it now, more than ever, because I’d forgotten the sheer risk of it.

Commissioning money and artistic trust can make you complacent, as well as furthering your career. That probably sounds ludicrous, patronising, selfish and insulting to some of you, and utterly naïve, but I want to be honest. That’s the whole point of this project, and of this section of the List.

I am being paid to take a creative risk. Thousands aren’t and their risk is so much greater. So if I don’t use this time to take my own creative risks, it’s a massive waste of money. Your money. I am answerable to no venue or theatre. This might well be a paid gig, but it’s also a responsibility and a privilege. I need to do more than what I already know how to do.

The stakes are high. And I need to start reaching higher.