(Documentary photograph by Roger Deakins for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts)

Hefted is a new play developed in partnership with Beaford Arts and supported using public funding from Arts Council England. It’s an epic story in nine scenes, hurtling through 600 years of life in the dynamic landscape of North Devon, taking audiences up to the present day and beyond into the future. It was directly inspired by oral history collecting, and work with local schools and communities. Here’s how the research informed the writing…

I’m sitting in a cottage in the tiny village of Lee on the coast of North Devon, on a freezing cold but beautifully clear morning in November 2017.

With me is one of Beaford Arts’ oral historian volunteers Malcolm, and across the table from us – past the carefully prepared collection of old maps, reference books, biographies, black and white photograph albums and newspaper cuttings, and the pot of tea and plate of biscuits that awaited us upon arrival – is Colonel Bob Gilliat, ex-warden of Lundy Island.

Over the course of a few hours he shares his recollections.

He remembers how the swans only flew over Lundy when there was a funeral, and how the small community of inhabitants learned to work together within the island’s limitations. He chuckles at being asked by visitors what there was to do on Lundy, and the pride he always took in his answer: ‘nothing – that’s the beauty of it’.

He also tells us how he saved a sheep from choking to death on a plastic sandwich wrapper left behind by a tourist, but in the same stroke was also amply prepared to kill a wayward canine with his shotgun.

It had been left to run on the beach by sailors warned once already about mooring without permission. Dogs bring disease – Lundy was too vulnerable to be put at risk.

I was mesmerised.

(One of the beautiful thatched cottages in Lee)

Over the next four months of my playwriting research, which would ultimately lead to the writing of Hefted, these deep connections and contradictions between nature, humans and landscape, past present and future in North Devon, were echoed again and again.

Across twenty-five other oral history interviews, one-to-one conversations with Devon Wildlife Trust, the UNSECO Biosphere Reserve leads at North Devon County Council, Green Party councillors, local historians and geographers, and via creative workshops with primary school children in High Bickington, a local history group in Hatherleigh and an amateur drama group in North Molton, I saw a repeated theme emerging.

North Devon and its inhabitants – whether nine or ninety, natives or incomers, farmers or teachers – were inseparable from the landscape.

(Ilfracombe on the North Devon coast – nature and homes side-by-side)

Hefted is gearing up for a professional and community company co-production this winter, and was directly informed by these activities. It was also directly informed by the getting to and from such activities and a steep learning curve around North Devon weather and terrain!

I got my trainers completely ruined whilst going off-path near Dolton and ending up in some wetlands, I tentatively nudged my car at 10mph through dense fog near Morte Point on a wet January morning, and I almost crashed on the link road whilst staring at the wind turbines at Beaple Moor.

(Spot the city-dweller – doh!)

I got buffeted by wind and spray on a dark December dusk walking at Hartland Quay, I wandered to Crow Point and felt like I’d arrived at the beginning of creation itself, and got helplessly frustrated on one-way roads trying to find parking in Barnstaple, before being blown away in the North Devon Museum by the geological strata still informing the land’s use and shape today.

I’ve always tried to embed myself in research for my writing, but this was on another level.

(The haunting gloom and visible geology of North Devon in Hartland Quay)

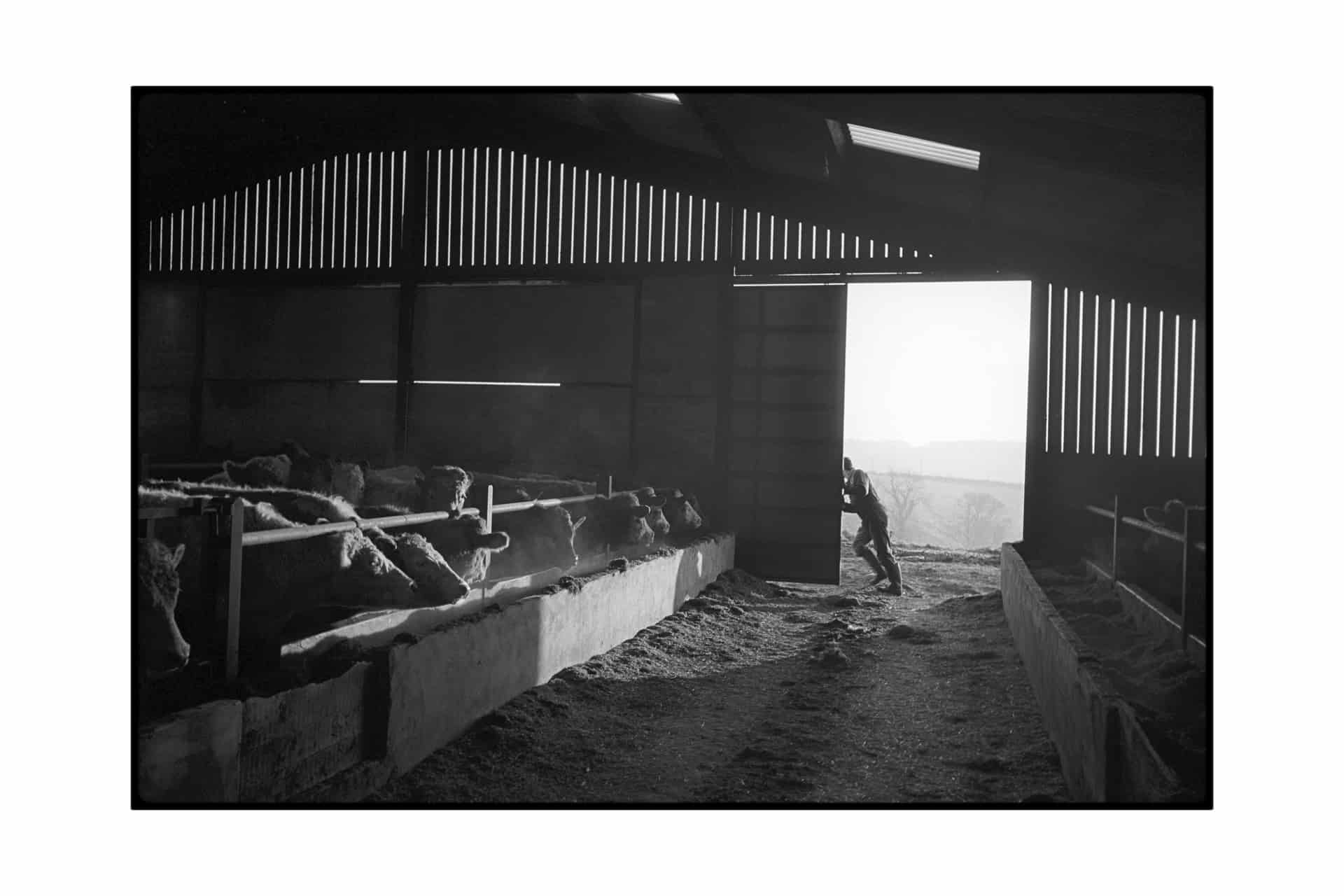

Gluing my research together was a bigger project of Beaford’s called Hidden Histories, at the heart of which is the digitisation of thousands of unseen black and white negatives taken by the photographers Roger Deakins and James Ravilious, who documented rural life in North Devon between 1972 and 1989.

All the people featured in the oral history interviews had some form of connection to these newest photographs. Some had relatives in them. Others lived in the locations.

(Photograph by James Ravilious © Beaford Arts digitally scanned from a Beaford Archive negative)

A selection of images came with me to all the interviews, prompting discussion, memories, sights, smells, sounds, experiences and stories.

As a writer new to his subject matter, I always find myself eager for authenticity. Oral histories in combination with Deakins’ and Ravilious’ images were a direct route to the authentic.

Devon dialects, rituals, professions, lifestyle, culture, trade, mythology, you name it – they were all encompassed within these incredible conversations, prompted by the hypnotically evocative photographs.

Oral history was a very new departure for me in terms of research for playwriting. I’ve always tended towards interviewing specialists about very specific professional practices – synthetic biologists, neuroscientists, Korean peace workers, parkour athletes, to name a few – but here, the specialism was just having lived somewhere particular for a period of time.

The specialism in oral history is the whole person and their lives. Getting an ‘angle’ was much more difficult in interview and sometimes wasn’t appropriate. I had to slow down, listen more, divert less. It made me more attentive, more open, and less assuming.

There was also a responsibility to ‘the archive’ too – in the nine interviews I led, I was responsible for creating a document of public record as well as researching an idea for a play.

I wasn’t necessarily able to transgress, interrupt, cut short or trail off into the minutiae of a particular area of interest relevant only to a tiny part of the play growing in my head, safe in the knowledge that nobody else would ever hear the recording.

(Photograph by James Ravilious © Beaford Arts digitally scanned from a Beaford Archive negative)

But the general knowledge I gained from the oral history interviewees – about lives lived, family sagas shared, broad experiences of landscape and nature in North Devon – gave me an excellent counterpoint for my own ‘off the record’ research interviews.

The oral history experience informed a line of questioning for them that I’d never have thought of otherwise. I could compare past experiences and ideas from an archive of human experience, and wonder openly about the present of the landscape with those who were intimately involved in curating its future as politicians, scientists, ecologists and geographers.

Alongside this I snapped photos, read books about local geology, listened to economists on YouTube talk about ‘Green Capital’ and tried to get my head around the vast long-term ambitions of the biosphere in North Devon.

(Nature and human intervention – the wind sentries on duty at Beaple Moor)

Then there came the point in my playwriting process where I had to stop and take stock.

Read back through all the notes, sink back into all the photographs, revisit everything and pull out the biggest connections and elements that might help bring form, story and structure to a play.

There were three elements that leaped out, and the first was transformation.

I came across the word ‘hefted’ during an oral history interview in Dolton with a woman in her eighties, who used it to describe her relationship to the village. She was brought up on a farm around half a mile from the village centre.

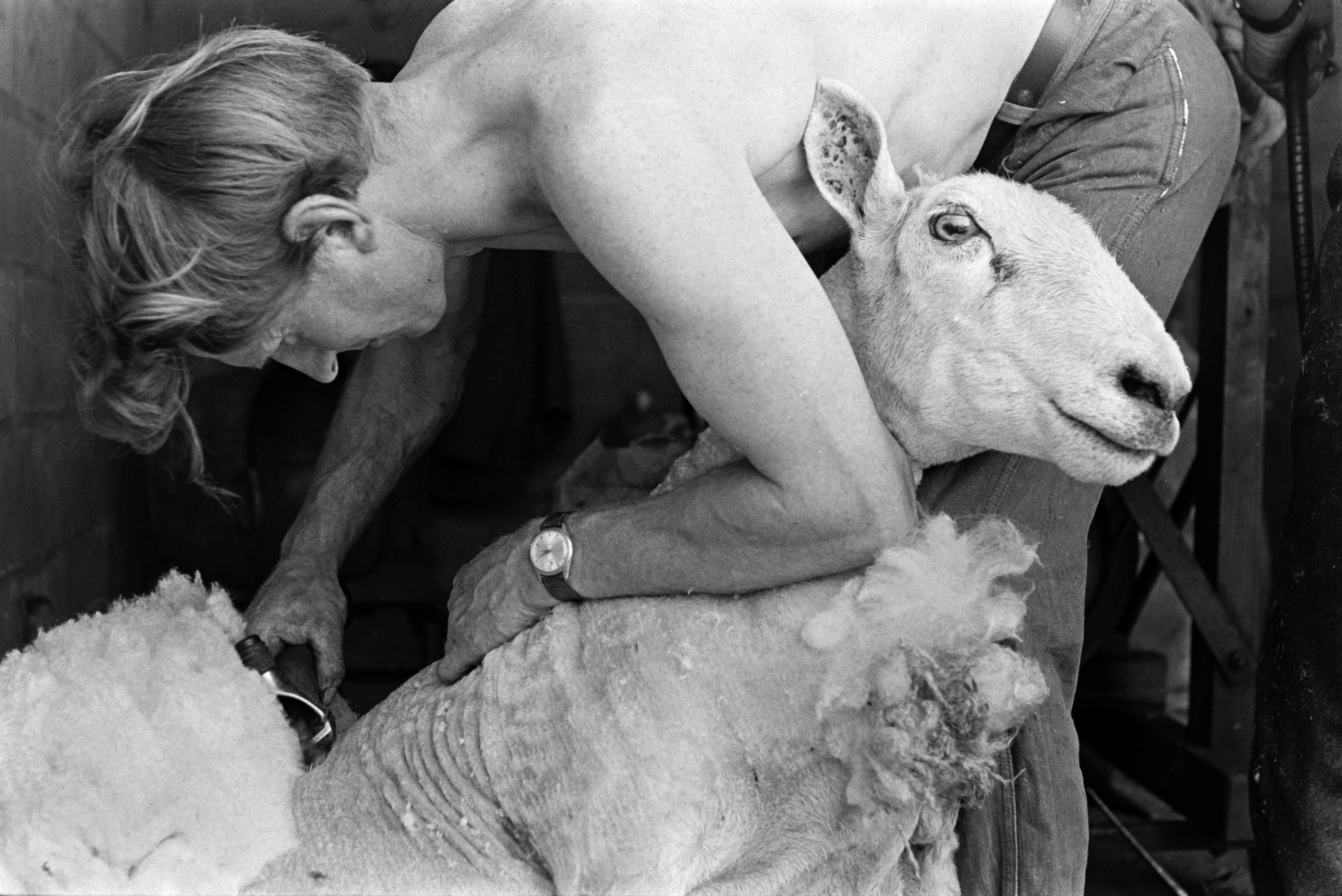

The ancient practice of hefting sheep – or ‘learing’ as it would be better known in North Devon – involves generations of ewes and their offspring learning the natural boundaries of their habitat. Incredibly the sheep can not only recognise this habitat, but also physically and even genetically change to live more effectively within it.

The metaphor this interviewee found to describe her relationship to Dolton took direct inspiration from nature. She made sense of her own experience by transforming my understanding of what she was trying to communicate: that she was almost umbilically connected to her immediate environment.

(Halsdon Nature Reserve, not far from Dolton)

Similar moments of ‘transformation’ were one of the most common features I came across from interviewees.

A man from Woolacombe remembered drying out his blazer by the school boiler after a torrential downpour, likening it to cormorants on the beach drying their wings in the breeze.

A woman recalled waking confused in the middle of the night as a child, to the sound of poultry being slaughtered – only to realise it was the sound of her dying grandmother.

A social worker remembered offering home-care support to an isolated farming couple that struck her as ‘seeming to have grown out of the landscape’. Another interviewee, upon being asked what changes she’d noticed in her ninety years of living in North Devon, drew on the baffling and seemingly super-human efforts of her father in transforming the farm’s fortunes.

(Documentary photograph by Roger Deakins for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts)

Transformation has become a leading idea in the stories of Hefted. I’ve tried to explore through theatrical imagination how landscape, nature and humans might vividly intertwine, in ways that entertain both mystical and supernatural elements.

The second connecting element from my research was how time was experienced in North Devon. Andy Bell, UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve Coordinator based at North Devon County Council, talked about the route you can take through Braunton Burrows as ‘literally walking through time’ as you track nature’s inevitable evolutionary march from colonising plants in the sand to rich woodland.

(The shifting sands of the dunes at Braunton)

On a more domestic level, the farming families I spoke to described the structure of the normal farming day in the 50s, 60s and 70s around set mealtimes, and the farming year around established necessary routines and rituals.

Then there were the anomalies of time – a farmer’s wife in King’s Nympton remembers double-summertime-hours being introduced during World War II.

Confusion was wrought among the poultry of her farm, awoken an hour early by the cockerel in the dark which then attracted the fox (who was still awake instead of safely asleep) and then slaughtered them: a vivid warning against messing with nature’s clock.

North Devon was repeatedly referred to by both natives and incomers as an anachronism: the land that time forgot; the forgotten land between the moors; that there were farmsteads in the depths of the countryside one might still stumble across that had escaped the progress of time.

Ravilious’ and Deakins’ photographs provided frozen moments of time, inviting a tapestry of sounds, smells and movement to form in the viewer’s imagination. Then there was the interviewee who commented upon ‘the dementia of North Devon – a landscape forgetting itself.’

(Demolition of a cottage for road widening, 1981: Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts)

Hefted has been deliberately structured around a series of scene snapshots across six hundred years, each set in a different part of this diverse landscape, hurtling the audience through a journey of time that connects the ancient, the modern and the unknown future generations of the region.

The final element connecting the research was the sense of exceptional endurance in North Devon. From the sheer work-rate of farmers in all weathers, to the determination of those who’ve shaped the landscape to serve human progress (and those who’ve sought to prevent it, in favour of preserving the landscape), there is a sense of determination, rigour and inventiveness.

A ninety-three year-old ex-farmer scoffed at the very idea of having taken holidays in his youth. A smallholder near High Bickington tries to capture for me the indescribable sleep-deprivation of lambing season, when life-and-death stakes rest on a couple of hours’ rest a night for a month.

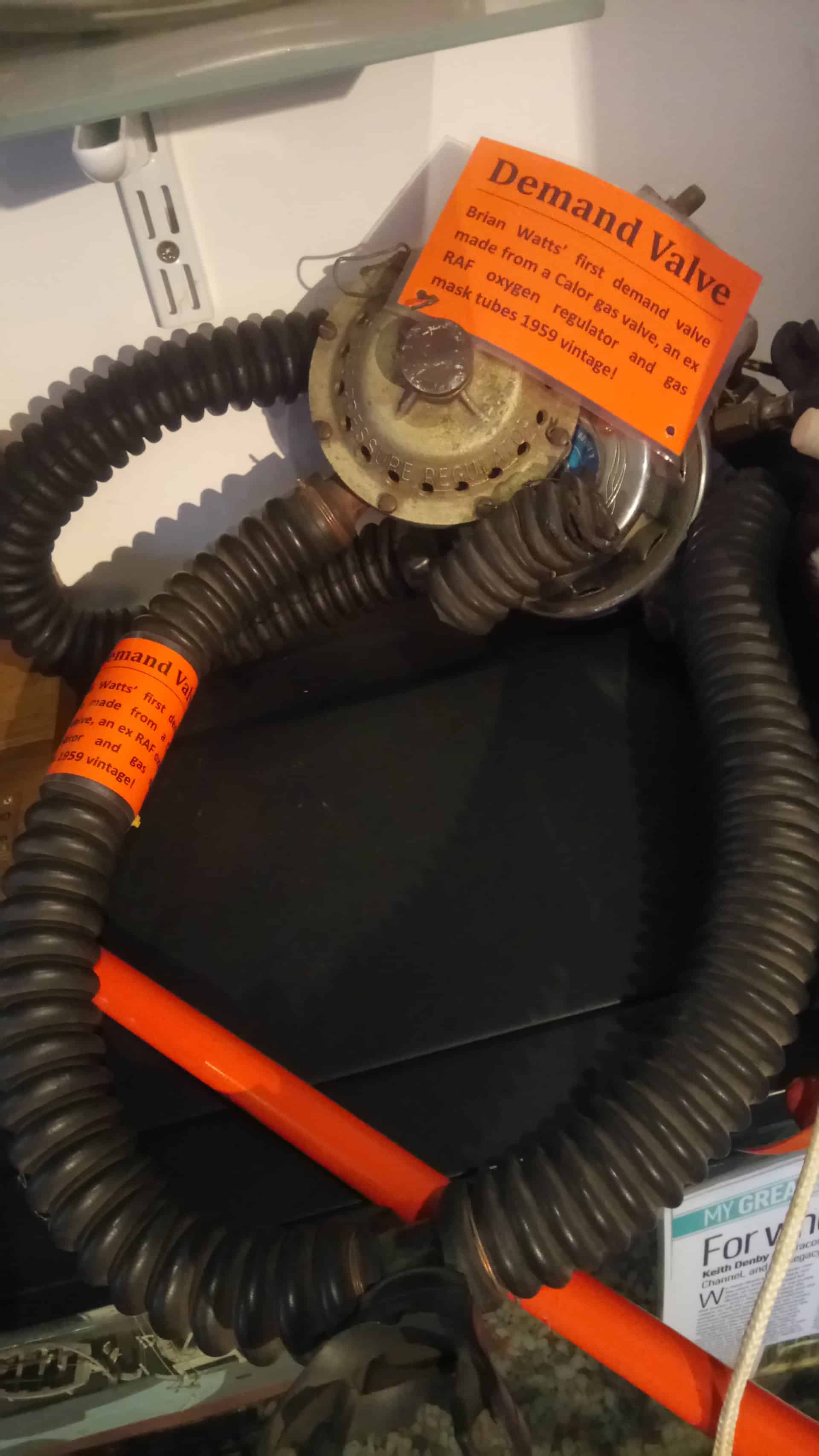

An eighty-two year-old sub-aqua expert in Ilfracombe shows me his first ever aqua-lung, built from an ex-RAF oxygen regulator, a Calor gas canister valve and a gas mask tube.

A daughter remembers her ‘superhero’ father’s hands freezing to a metal milk churn, finally (begrudgingly) agreeing to wear socks over them the next day, despite never having worn gloves his whole life.

North Devonians do not give up.

(Brian Watt’s first sub-aqua lung – fully recycled materials!)

This spirit of survival has permeated Hefted to its core – it’s a story of how the people have endured alongside the landscape – but it had to be pitted alongside a question that kept cropping up for the entire four months: if you’re born here, do you stay or do you leave? That ongoing tension is one of the driving forces behind the play.

All of these central ideas, an initial storyline, and the first draft were tested out with North Molton Amateur Dramatic Society (NOMADS).

This is by no means a stress-free experience for a writer from metropolitan Bristol, turning up at a community hall in front of thirteen North Devonians with 82 pages of script, professing to reveal or communicate something about their region that they didn’t already know.

But NOMADS were fantastic. They guided me through using dialect, offered appropriate names for characters, questioned with pinpoint accuracy my facts and dates and geographical reference points: details that I’m still refining now in a final draft.

They were the first audience of Hefted really, and if their enthusiasm and support is anything to go by, I’m incredibly positive about its potential impact on audiences.

(In rehearsal for a script reading with the performers and director, Swimbridge Jubilee Hall)

When we shared a new draft in Swimbridge in early July, we were delighted to have so many people approach us ready to reflect back their own stories and tales of belonging in North Devon too.

We already have exciting future plans for the piece too. Beyond its stage premiere we hope to record an audio version that can be listened to online or even on location, in landscapes that echo the settings of the scenes.

What I’d hope audiences get from Hefted is a chance to experience where they live in a new way that is familiar and celebratory and surprising – and a little provocative too. To have their beautiful and mysterious landscape, its history and its future reflected back at them with a sense of theatrical adventure, mythology and magic.

(Documentary photograph by Roger Deakins for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts)

This is what Ravilious and Deakins opened up for me with their incredible images. I can’t wait to see it reach its final stages in production.

The oral histories and previously unseen images from the Deakins and Ravilious collections will be available online at beaford.org in mid-September.

Enjoy this blog? You can get more insights and receive weekly updates on competitions, awards, submission opportunities, jobs, training and workshops by signing up to Lane’s List – every Thursday, 50 weeks a year, to your inbox.