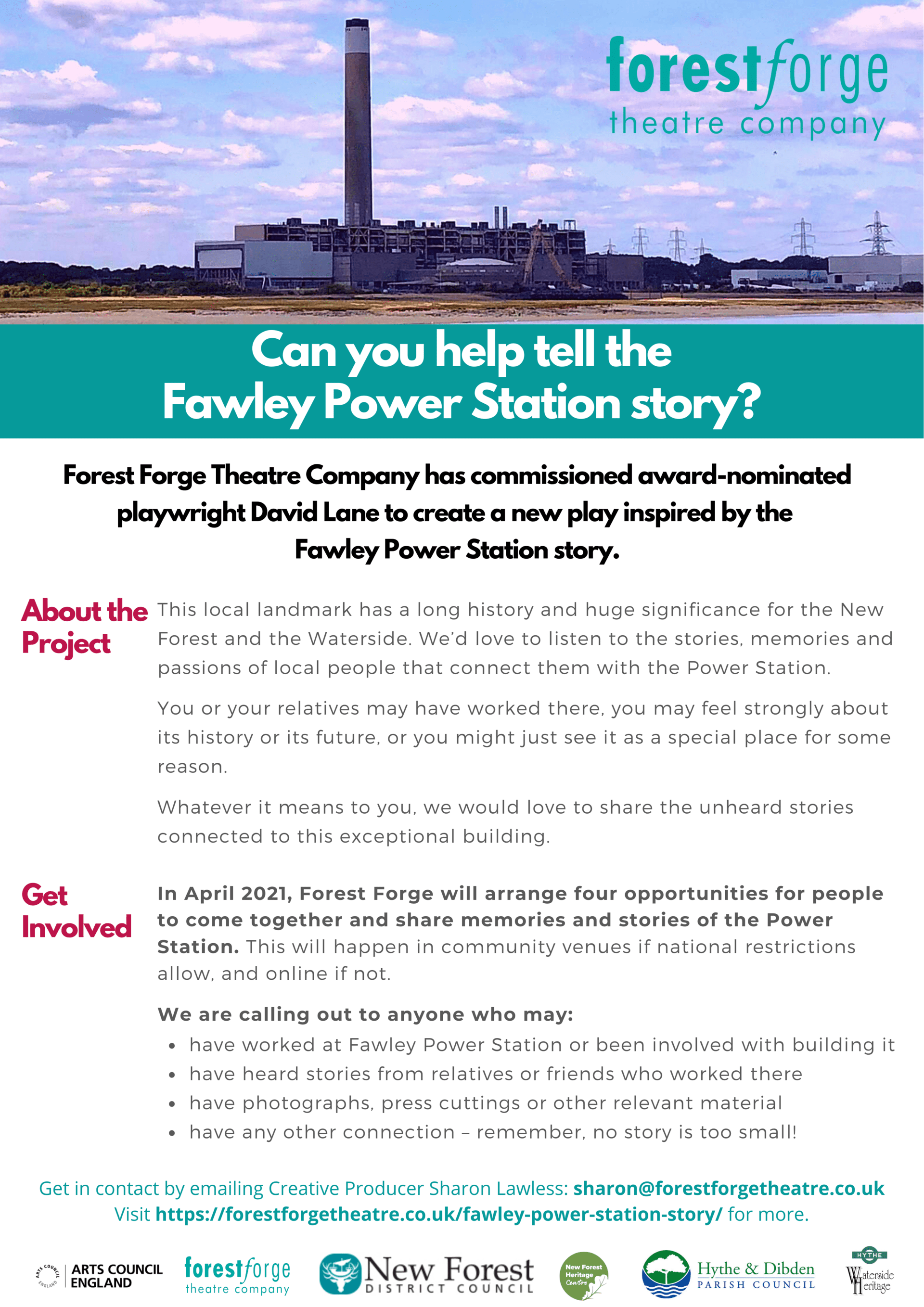

I’m pressed up against a grey wire fence adorned with barbed-wire coils, 24hr CCTV notices and a thin layer of beige dust. There’s the muted rumble of demolition being carried on the breeze, an occasional security van slowing down to clock my presence as I snap photographs with my phone, and the sense of something ending and something beginning in the air.

This is the site of Fawley Power Station in March 2021.

Developers call it a brownfield site. But it’s still Fawley Power Station. Or, at least, some of it.

It’s also the central focus for a new community-inspired play funded by Arts Council England, commissioned by Forest Forge Theatre Company, and seeking to unearth, explore and champion not only the stories that surround the power station from the local community, but also its wider significance in a much longer and ongoing story: one of energy creation, rural transformation, the nature of progress and national industrial identity.

My work as a playwright is hugely research-led.

I work through archives, historians, conversations with relevant experts, site visits, and in the case of this project, engagement with our partners the New Forest Heritage Centre and Waterside Heritage Centre.

I’ve read English Heritage listings reports, archival guides to power station heritage, watched lectures on power station landscaping, interviewed architects and councillors and planning officers, and most importantly, pursued community engagement – finding opportunities to hear from the people who worked there, still live in the area, and know the deep significance of the power station itself.

But how did we come to this project, and why?

In February 2020, the New Forest Heritage Centre hosted a pop-up gallery of photographs, stories and a short play comprised entirely of community voices, which the theatre company and I had brought together from one simple invitation: bring us your photographs of the Waterside from the last 100 years and tell us your stories about them. The exhibition was engaged with by around 4,000 people in total.

The stories we gathered showed us many things, but one in particular: the unique and fascinating blend along this relatively short strip of land of rural, marine, civic, military, agricultural and heritage land-use. The Waterside is a roughly 22-mile area of coastline stretching along Southampton Water between the town of Totton and the geographical feature of Calshot Spit. Its identity, architecture and community has been constructed and impacted by industry of all kinds – boat building, chemical industries, oil refineries, to name just a few – and of course, the generation of power.

Most of all, the story that everybody was commenting on was the proposed development of Fawley Waterside – an entire new ‘smart town’ to be built on the site of the power station between 2022 – 2034.

The scheme’s planning proposals went through in July 2020. They’re headed up by Aldred Drummond, who saw a portion of his family’s Cadland Estate compulsory purchased by the government in 1953, in anticipation of Fawley being proposed and built.

In 2015, Aldred bought back the 300-acre site from the then private owners RWE/npower. Fawley Waterside is his vision: a sustainable working town for employees and their families, economically underpinned by a 5G, marine and digital industry-focused centre of excellence. It comes with challenges – the tricky transport infrastructure and acceptance of the intended architecture is still dividing people now.

But development of technology and business is no stranger to the Waterside.

A hundred years ago in 1921, a tiny oil refinery was built at Fawley by a company called AGWI: the Anglo Gulf West Indies Petroleum Corporation. They would later become Exxon Mobil, trading in the UK as the more familiar Esso, and then expanding operations in the area five-fold by 1951 to create one of the world’s biggest oil refineries. Pre-fab houses popped up. A sports and social club was formed. An entire Waterside community was created. The refinery is still going strong today.

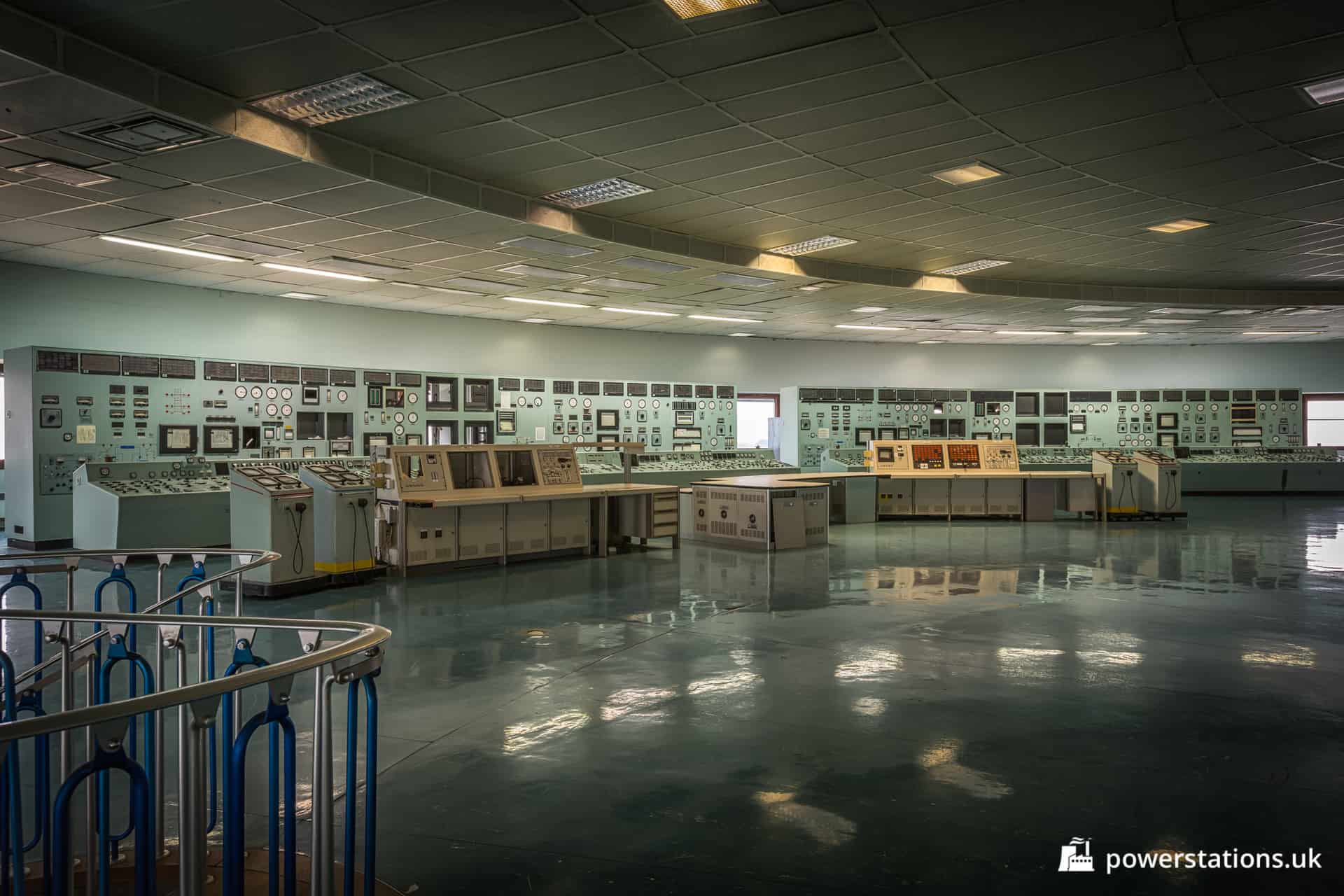

Around a decade later in August 1961, the newly-formed Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) made an application to the Minister of Power for a license to build Fawley Power Station: at the time, the world’s biggest oil-fuelled power station and later to become the world’s first computer-operated one.

But Fawley was just one power station in a mammoth programme across Britain in the 1960s that saw the development of huge new architectural constructions, intended to supply and celebrate the country’s energy independence, and with a particular sensitivity to landscaping approach.

Section 37 of the 1957 Electricity Act outlined that power stations were built with respect for the environment in which they were placed – one of the biggest ever changes impacting the building of power stations. Leading architects of the time were brought in by the CEGB including Dame Sylvia Crowe. Power stations were moving away from the brick-cathedral Bankside template, and into the new brutalist-architecture inspired age of concrete and steel edifices.

The results at Fawley from renowned architects Farmer and Dark were one-of-a-kind.

Fawley Power Station officially opened in May 1971, though began supplying power to the National Grid from 1969. It was hit by the oil crisis in 1973 but then operated at full capacity in the year of the miners’ strike in 1984 producing a whopping 400% more energy than its annual average, and becoming a base-load station for the National Grid to help keep the country’s lights on.

A decade later, following a failed attempt to build a ‘Fawley B’ coal-fired station on the same site in the late eighties – which had surrendered to privatisation and a huge public outcry by 1989 – two of the oil-fired station’s four 500MW Parson Turbines had been mothballed.

A year or so on from then in the mid-nineties, it was listed as one of the most polluting power stations in the UK. At the beginning of the millennium, new emissions directives from the EU condemned it to its final 15,000 working hours. Fawley was officially decommissioned 44 years later in March 2013.

But in some ways, that brief beginner’s history – which only scratches the surface – is also the start of a much more complicated story across the last eight years, which brings us up to the present.

It’s a story of a physical archive of items and documents from the power station scattered out across ex-employees and four different archival holdings at the time of its closure.

It’s a story of optimistic exhibitions of what the future might hold back in 2013, then of simultaneous applications to English Heritage in 2014 to both list (protect indefinitely) and make immune from listing (open up for demolition) the power station buildings.

It’s a story of the New Forest District Council’s own listing of the site as a prime development area for new housing in its 2016 Local Plan (rather than its recognition, as some wanted, as a heritage asset).

It’s a story of the National Park Authority’s strict regulations over building developments creating a death sentence for the chimney.

It’s a story of the first dramatic explosive events which saw this extraordinary glass-clad building – stripped of its glass at the time of the video link above – destroyed forever.

And in terms of the new development, it’s a story now of ongoing long-term concerns about transport infrastructure and local purpose and relevance, next to excitement and optimism for the development’s economic uplift of the area, tech prowess and renewal of natural wildlife habitats.

There is a deeply sincere and passionate respect for Fawley Power Station in the local area.

There’s despair and frustration that architectural features like the magnificent 198m chimney – now home to itinerant peregrine falcons – and the futuristic ‘flying saucer’ control room – now home to Fawley Waterside’s administrative and marketing suite – will be gone within a year. There’s a community that really love the building, and what it represents to them.

I could go on. There’s a myriad of even deeper complexities in these stories that there isn’t space to go into here. And as I move out of desk-based, archival and specialist interview research, and towards our planned online story-sharing meetings with ex-power station workers and local community members in April, I remember I’m also just interested in the basics.

What was it like to work there? What did it smell like and sound like? What was the social life like? What are the anecdotes and tales and feelings I can’t ever discover from just reading things?

If there’s a human story that pins it all together, it was identified by the play’s future director Lucy Phillips at Forest Forge, as we chatted through my findings yesterday from the last couple of months.

I’ve been contacted by a lady who lived and worked on a farm overlooking the power station’s site before it was built. She remembers ‘having her playground taken away’. How the cattle were affected by the constant noise of the piledrivers. How the place where she learned to swim, fished with her father off the little jetty, and watched the wildlife, was taken forever.

Fifty years later the owner of that land, who had no say in it being removed from his family’s ownership by the government’s ambitious new energy creation plan, is taking it back.

It’s a story of desire – of having the things we hold dear taken away from us, and how able we are (or not) to fight to win them back: and what options we’re faced with when all that’s left is ghosts.

I haven’t formed strong opinions yet, or fallen down on one side or the other about the station’s future. My role is to consider stories like those above, from very different perspectives, with equal weight. That conflict is what will make a drama interesting, rather than one-sided.

Standing by the power station fence this week however, I did notice I was hugely disappointed that I would never get to see the incredible glass portion of the building up front. Never get to walk inside the huge hall. I felt that and recognised I’d started to form a relationship with this infectiously fascinating place.

The reality of that hall now is that a quarter of it remains, its pipework and guts spilling out, as if a giant’s carving knife has sliced through and swept away the rest. But the ghost of it is there.

As the building gradually ebbs away, part of the job of this play is, I hope, to allow those ghosts to speak.

———————-

If you’d like to get involved with the project, tell us your stories, share your memories or anything else relating to Fawley Power Station, please contact Sharon Lawless at Forest Forge Theatre Company on sharon@forestforgetheatre.co.uk

We will be holding online sessions for community stories to be shared and celebrated towards the end of April. If you’d like to take part in these, please email Sharon.