This blog was originally published in Summer 2015.

I’m now two-thirds through my Arts Council and Peggy Ramsay Foundation-funded Protected Time to Write project. This is blog 7 in a series of 10 tracking a playwright’s process from initial ideas to first draft, in a bid to share some of the learning that’s coming out of it.

You can click on the links here for Blog 1, Blog 2, Blog 3, Blog 4, Blog 5 and Blog 6.

Blog 7 first appeared on Lane’s List on July 13th 2015.

It’s starting to look like one of those play things now…

“Draft” – A Definition from Dictionary.com:

1. a drawing, sketch, or design.

2. a first or preliminary form of any writing, subject to revision, copying,etc.

3. act of drawing; delineation.

I’m probably two-thirds of the way through writing what I’d call a rough draft now – a first draft being the Holy Grail that marks the end of my funded project – but it also feels like I’m only approaching the beginning of what this play might be once it’s rehearsal-ready (because ever the optimist, I’m deciding that at some point it will be in a rehearsal room somewhere, some day).

Despite weeks spent on process and planning, you only begin to understand whether your play is going to work once you start writing it in scripted form – everything else is about whether or not it works ‘in principle’.

I have a habit of wanting to trust that good writing can sell those ideas which, on paper, look less than credible or just too mind-bendingly complicated to attempt. This might be foolish, but it also means you do a lot of learning from your mistakes and a lot more pushing yourself places you might not otherwise go.

I much, much prefer re-writing to writing. This is probably the dramaturg in me – with my own work, I find it easier to set a sharp and specific tool to something that’s finished than I do generate material from the bottom up.

Maybe it’s like a potter – I love the feel of the clay in my hands, having a pliable but mis-shapen form gripped in my palms that is finite in its mass, but is being gradually re-shaped and re-shaped as I try to get it just right.

At this moment however, I’m still adding to the wheel and my foot is still pummelling away. And already, around the bottom of my wheel lay lumps and shards and even whole pieces that have spun off in the process; in addition, in the bucket of clay I started with are whole discarded segments I haven’t even thrown on yet, and probably won’t. I do know that later, however, all of this material will help create my routes in for rewriting.

For now though it’s about writing. A friend asked me how the writing was going the other day, and I decided that for me (and now let’s delve into another convoluted metaphor) that writing a play was like building three houses. At least, that’s how I’d describe the process on this project.

House One you conceive as an architect, going from the foundations up to the roof. It requires you to ask the big underpinning questions, get the core idea, find the beating heart – what is going to hold up this mammoth structure and keep it stable and firm: what does it rely on? How many rooms? Where are they? Why are they there, and not there? What’s the décor and character of the whole thing? Much natural light, open and airy – or clinical and cool, closed off and mysterious?

This is the planning section, the creation of the blueprints – getting hold of a secure image and structure so that you can build it for real.

House One: 1. a drawing, sketch or design.

Writing a rough draft is House Two. This one you build from the top down, because the first thing you do is put a roof up so that you don’t feel vulnerable and exposed. Then you power through and finish one entire room (or scene). Probably the loft.

There. I’m safe. It looks like a house (or play) and I’m protected from the elements. Now I’ll build the room next door. Then the next one, and so on, but working downwards the whole time because – and this is where this (probably rambling) metaphor sprung from – I am building something the whole time, but realise that I’ll only understand what really holds it up and what shape it really is from the outside once I’ve finished it, and stepped back. I’ll probably only comprehend what should form that cement I’m fixing around the four big steel girders planted in the earth at the end of the play.

House Two: 2. a first or preliminary form of any writing, subject to revision, copying, etc.

The process of going from treatment/outline/planning to scripting will always require you to be creative, to adjust and re-think and discard and uncover new material too.

I think the roof-down image is simply a way of saying that until you have characters moving and talking and making choices and being compromised in moments of conflict and action, with the pressure building; until you see them as people, not abstracts; until they’ve revealed to you the true nature of their journeys, you can’t possibly know for sure what the foundations look like. You know in principle – but in the world you (and now they) are creating to inhabit? I don’t think you can. I think you have to get to the end to know where to begin. Begin what?

House Three: first draft proper. The one you’ll show theatres and directors who know nothing about you. This one you’ll truly feel like you can’t re-write anymore. It’s the one that carries your confidence in its crafting – in its walls, its furniture, its windows, its yet-to-be-discovered secret passageways. It’s a beautiful building.

That is clearly not the rough draft.

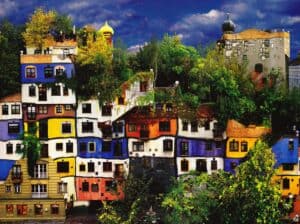

The rough draft, House Two, looks like the bastard child of The Hundertwasser House and the Sydney Opera House, with avenues of clunky but reliable post-war East Berlin communist housing woven in.

(The Hundertwasser House, Vienna. Bold ideas but potentially impractical)

So how do I get from House Two to House Three, and the end of the project?

I’ve managed to garner the services of twelve very generous actors and two directors (pah – one director darling?) to read and respond to a cold sight-reading of the rough draft.

Wow. There’s a sentence that fills me with dread and excitement in equal measure.

Every writer sits down at such a read-through wanting to hear the version of the script that’s in their head, because the version of the script that’s in their head is the one that’s got a set and costume and sound and four week’s rehearsal underneath it. The version you hear is a bald, raw and immediate response – for me, a perfect acid test of a script’s core strength: its story and characters.

The subtleties of form and tone and rhythm and language are only layers to enhance that core strength – and it’s one that you can and should test out early on, with a mixture of people whom you trust, people who know a bit about your play, people who know nothing about it (but that you still trust) and people you’ve never worked with before.

I’ve managed to get hold of a range across the board, and the knowledge that they’ll be around a table in two weeks reading the yet-to-be-completed-play is a really helpful pressure, and is I hope raising my game a little.

Meanwhile I’m still clattering through House Two, the plans of House One ripped and smudged, stuffed in my paint-spattered back pocket whilst I slap on slightly crap cement and broken bricks and seal up holes with the equivalent of dramaturgical Polyfilla when my brain can’t quite summon the totally perfect structural solution: BUT – I trust that when I hear it, I’ll find out what I need to know.

What I’ve learned in the latest section of this project is that there is no way to keep calm through the writing of a rough draft. I’ve felt everything on the scale from utter excitement to anger at myself – but I have always kept moving forwards because that’s the only answer to getting House Three ever built. To build House Two first.

Then to look at it afterwards, invite some people to come and take a look around, take a deep breath – and listen.

Then you can begin making the detailed choices that really define and delineate the work.

House Three: 3. act of drawing; delineation.