This Halloween at dawn, on the Waterside of the New Forest in Fawley, a 198m chimney stack belonging to what was once the world’s largest oil-fired power station will be razed to the ground.

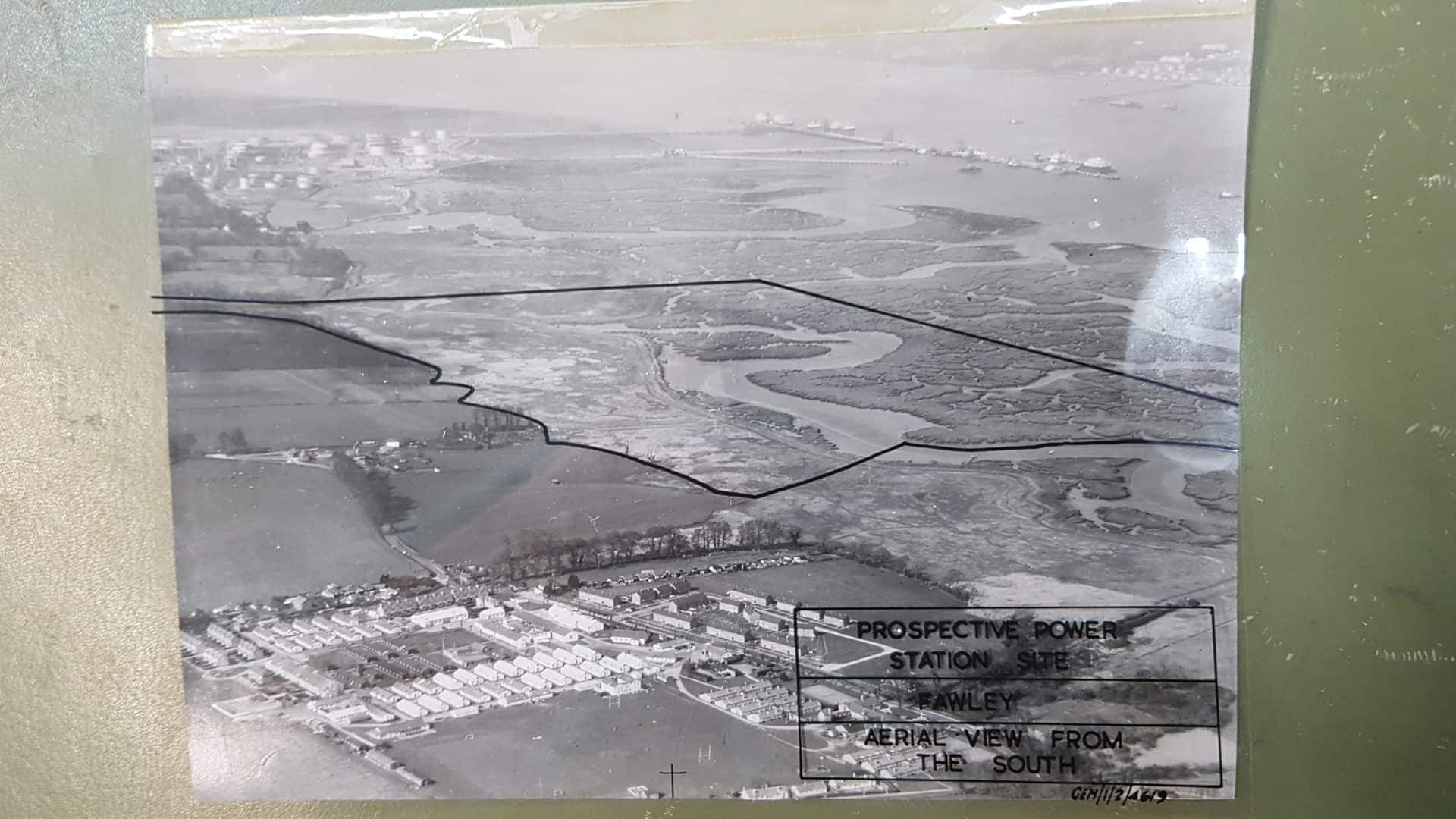

It began when the government started to reclaim land from the Solent marshes in 1952 and will reach an end in 2022 when the site is finally cleared.

This history is the inspiration for my new play being created in collaboration with the New Forest’s own Forest Forge Theatre Company, New Forest Heritage Centre, Waterside Heritage Centre and advisor in creative histories, Dr Will Pooley at Bristol University.

It’s been inspired by extensive archival research and over twenty interviews (and counting) with ex-workers and members of local communities.

Shortly after the long-anticipated and appropriately haunting demolition date was announced – along with its enforced blast exclusion zone, in a bid to deter local onlookers – a ferry company began advertising a dawn cruise with coffee and breakfast, so passengers could watch the seminal event from Solent water.

It sold out in days.

Also, I say ‘local onlookers’. I’ve heard of people wanting to pilgrimage from much further afield to witness this emblematic piece of world-first industrial heritage come down.

There are people overseas desperate to obtain a piece of the chimney – perhaps their own way of memorialising the event – before it disappears. Some are camping out on Calshot Spit across the water the night before, essentially leaving themselves to be ‘locked in’ by the exclusion zone, to gain the best vantage point for the detonation.

In the last few weeks, the Facebook group dedicated to ex-workers of Fawley Power Station has burst into a proliferation of stack images and videos, taken at sunset, dawn, in mist and clear blue sky, from boats and planes, close up and as far away as the Isle of Wight.

This is not a chimney stack. This is a piece of people’s lives and heritage.

I’ve read through communications at the National Archive from 1961-2 between the Central Electricity Generating Board and the Ministry of Power, when the station was originally proposed (including the original opposition letters from local tenant farmers, Hampshire County Council, Winchester and New Forest Rural District Council).

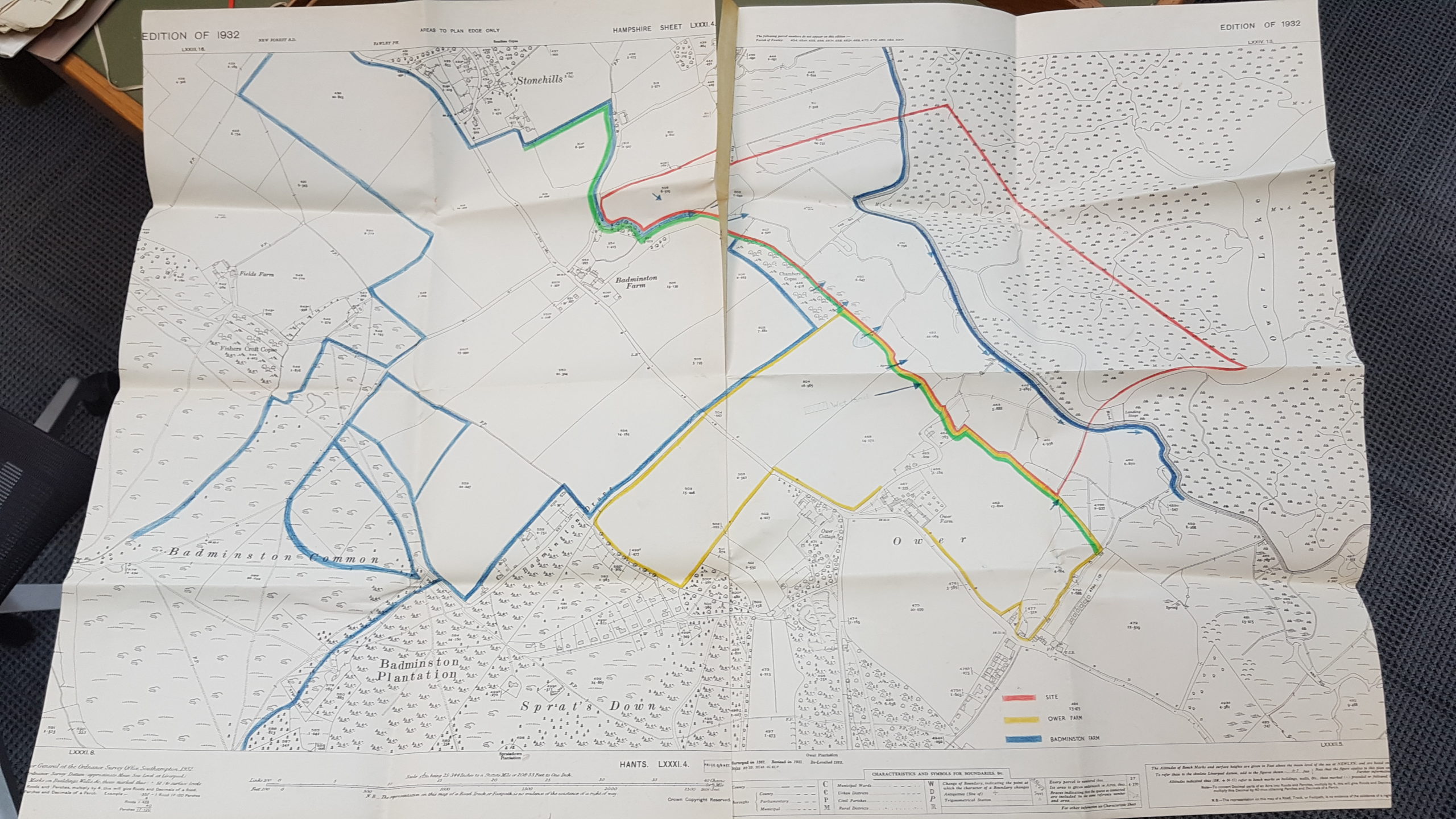

I’ve pored over their planning maps and the images and arguments, and the bargaining that went on to get the power station planning over the line.

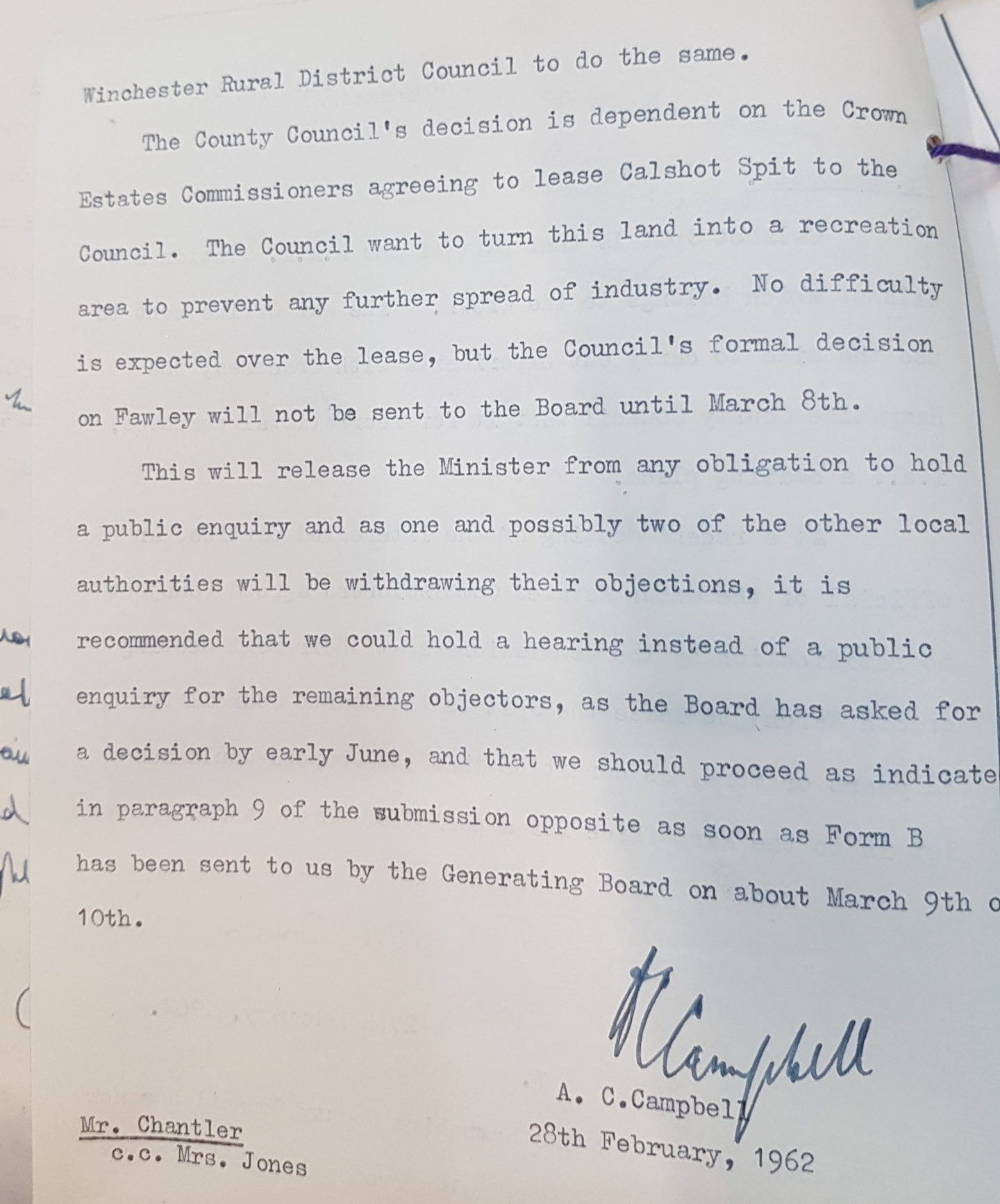

For example – knowing full well that Hampshire County Council (HCC) as key objectors to the power station also had a desire to obtain Calshot Spit to build a leisure amenity, the government offered it to them, on lease from the Crown.

This was in return for three years’ more use by the Ministry of Defence and – much more importantly – a withdrawal of HCC’s objections to the Power Station. Other objections had been properly mitigated, but this economic bargaining was key.

It’s on the record (above) that there was an assumption if Hampshire County Council fell, the councils beneath them also would fall. Which is exactly what happened, avoiding a public inquiry and instead quickly ushering the power station in via a tiny hearing at Jubilee Village Hall in May 1962.

Similarly, when Cadland Settled Estates owner Maldwin Drummond was fully assured that any breaches of the planned site’s development onto his own land would be recompensed, he withdrew his own (triple) series of objections – and many of his tenant farmers then followed suit.

I’ve delved into the roots of the powerful civic protests that were key in diverting a coal-powered ‘sister station’ being built on the same site in the late 1980s.

I’ve got embroiled in political debates about the fate of the station since its decommissioning in 2013, grappling with the ethics of why English Heritage’s judgements of value can’t hold the same weight as those of the people who built and worked at the station itself – and on, and on.

To be honest, with the amount of research I’ve done I could probably write a mini-series for TV, several documentaries, a history textbook, or a series of screenplays.

(Original hand-drawn map from CEGB / MoP showing site boundaries of local farms and the power station [in red])

But the challenge is to get a sense of this place into one 90-minute live performance. The aim has to be the telling of a story that captures the meaningfulness of Fawley, as far as I’ve understood it from the people who knew it best.

To do that, I’ve decided to focus on two stories. One is a snapshot story of a moment, the story this Halloween – a story about a moment of extreme and permanent loss.

The other is a long story of rise, fall and resurrection – the story of the site itself from the 1950s into the 2030s.

Once marshes, then a brownfield site, then a building site, then a power station, then a demolition zone, then a brownfield site again and next – by 2034 – a marine and digital industries exemplar town, this site is a metaphor for the cyclical nature of history, politics and business.

And at the heart of both stories is a tension between a learned human desire for progress, and an innate human yearning to arrest time itself. We want everything to be the same, yet everything will have to change.

(A hand-drawn acetate from the CEGB archive – past and future overlaid, showing the marshland that will be reclaimed to form the Fawley site)

Grief and loss demand humans stop and take stock; but also that we move forwards, in order to survive emotionally. Industry demands that we move forwards so that it can survive, but in doing so it inevitably leads to permanent and irrevocable human loss – of jobs, of communities, of buildings and of treasured memories.

When you throw these elements towards one another, and then put them on the shoulders of a single character, their competing demands become messy and complicated and strained and difficult – and to my mind, that’s what makes a great drama, because at the heart of it is a compelling human question – how do we survive great loss?

Right now, that feels like a question that is so pertinent to Fawley Power Station.

But to understand it fully as an outsider – which I am – has meant connecting with the history, which I always start with in my writing process. Only then can I access what’s actually at stake here. The stakes of this stack coming down on Halloween are intertwined with the architecture, the people, and their experiences.

(Collected staff photographs from the personal archive of Margaret Tillyer, Station Tour Guide 1972 – 2013)

So at this story outline stage, before I settle down to write a first draft, I know a few things.

The play is going to follow a single character called Eddie, from the age of 10 in 1951, sitting on a jetty with his best friend on what used to be the salt marshes at the back of Ower Farm. But he should be at his Mum’s funeral.

It will then move across twelve scenes until we hit 2034, when his grandson Charlie at the age of 41 is trying to fix a mysterious power outage at Fawley Waterside: one that has hit the very same site where his grandfather diverted himself from the grief of his mother’s death 83 years before.

Through all this, we follow Eddie’s grappling: his tussle with the need to keep progressing away from a place of grief, to move on – but an equally pressing need to stop, take stock, and recognise what he’s lost.

The longer this internal conflict goes on, the harder it gets – until a moment of collapse looks like the only option, and we’re brought to November 2021, just after the fall of the stack.

Often, only when everything collapses, are we forced to confront our truths.

Through the play we’ll also hit vital turning points in the station’s history including its construction, the first unit contributing to the grid in 1969, the opening in 1971 and successes through the decade, the full-load miners’ strike year of 1984, the staff redundancies and down-scaling of 1995, the impact of the National Park’s creation on its later fate, its decommissioning in 2013 and its sale and development from 2015 to the present – then beyond, to the future.

Within all this there is of course also celebration, family, parties, community, success, fun, life and death. Fawley held all of this within its cathedral-like walls.

And I know one more thing – that the site itself has to have a voice.

I interviewed one lady who was a station tour guide from 1972 – 2013, and one of the last things she said to me was ‘remember – a power station is nothing but a convertor of energy’.

That’s really stayed with me: the idea of energy never going away, but just transferring, continuing, changing – haunting.

The power that live theatre brings is the power to voice the inanimate, to articulate deep ideas, to access stories that have never been told because they sit outside the real.

And that’s why a mercurial figure called the Watchwoman is also going to be in the play.

Inspired by the stack, she’s a character that is part-ghost, part-architecture, part-soothsayer, part-sage – and who guides and haunts Eddie throughout in equal measure, looking over him until he fully understands what it is he needs to confront. She too will fall – or perhaps just convert and transform all over again.

There are also plenty of stories on the cutting-room floor, numerous quotations and experiences and documents, all increasingly painfully jettisoned.

I came to realise early on during my research that the station’s history is not really collected in any organised way at all. This was part of the challenge when I began. And I’m not staking a claim to this play being the only thing that’s going to do that, but I am hopeful of it creating ‘a’ history. At the end of the day, history is just a version of the past in the form of a story, authored by the voices of those who are telling it.

What I hope has happened however – and what Forest Forge and myself will strive to continue with – is that it’s not just my voice shaping it.

Where I’ve arrived so far is absolutely down to the generosity of those contributors and their voices. When we come to sharing an early draft of the play, via an invited script-in-hand reading later in the year, we hope that as many as possible of the contributors so far can be there, so we that can all listen well – receive questions and comments from those who have genuine ownership over this site.

We want this play to be for them, but also to speak widely to new audiences. That comes from getting these next few stages right, and being bold, brave and compassionate.

(The interior of the flying-saucer control room at Fawley Power Station – still a futuristic amphitheatre itself)

I’ll be making the pilgrimage down to Fawley and will be fortunate enough to watch the event from the water (not on the demolition cruise – I wasn’t quick enough to bag a ticket).

I’ll be bringing my daughter too. My mother-in-law lives in Totton so it’s a family visit. (As an aside, in 1961 the Totton and District Trade Council wrote a vehement letter of support for the Power Station to the Ministries of Power and Housing, representing 2,500 Trade Union members from up and down the Waterside who recognised the need for investment and jobs in the area).

Anyway – my daughter was initially thrilled simply by the idea of watching something get blown up. But when she asked me why we were going, and I translated all of the above and the last nine months of thinking into a short explanation, she simply asked ‘why can’t they save it?’.

This is a question that’s been answered in multiple ways by various people – it’s too expensive to maintain, too dangerous to upgrade, too full of asbestos to allow anyone in, too out-of-keeping with the vision for Fawley Waterside, too intricately tied-up with land belonging to the National Park Authority and their regulations for the visual environment. To say the saving of the chimney is a moot point is putting it lightly.

An evasive answer – but in the long game of history and the even longer game of time, probably a truthful one – is that maybe, because sooner or later, everything has to fall. But it’s how we remember that helps keep things alive.

You might have memories or experiences about Fawley Power Station that you wish to share with the company. If so, we’d still love to hear them as we continue to develop the play.

You can write to us at Forest Forge: sharon@forestforgetheatre.co.uk