Let’s start with a couple of caveats.

Firstly, I know there’s no such thing as a passive spectator. The very phrase is a tautology: to spectate is to perform an action – of watching, witnessing, perceiving, interpreting, imagining and wondering.

Secondly, I’ve covered some of the ground below in a previous blog when working as a dramaturg with student companies, each insistent on the seductive properties of ‘immersion’, which can apparently only be achieved if you’re a spectator-participant.

There’s been a lot of mentions in the last 24 hours at IETM about the ‘void’ – this physical space between performance space and audience space, and how it really is something we should all be moving on from. We’re all connected and networked these days, so as with life, as it shall be in theatre. Close the gaps everywhere. No?

For me, the exhilaration in great theatre is when it reaches out across that void in spite of its apparent vastness, and closes it down through our collective imaginations. Also I’d claim that it isn’t a void in a conceptual sense, because it’s a full space for the entirety of a performance where the multiple conversations between performance space and audience occur.

The plays that achieve this are the ones that have sucked me in, immersed my imagination and transported me without even leaving my seat. Such is the power – and the craft – of theatre with depth, complexity and (more often than not) narrative, accompanied with visionary directing and performance. This is not exclusive to plays either (caveat number three).

The provocation within Generation 2 Generation: New Theatre Forms for New Audiences was that the next wave of theatre-makers is comprised wholly of digital natives, and to borrow a loose translation of a Japanese word, is ‘the generation that can do two things together’.

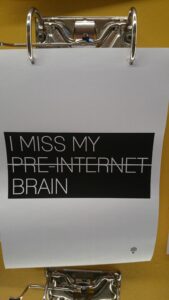

They’ve grown up in a digital landscape, are used to multi-tasking and cooperation, and are in the unenviable contradictory position of longing for uniqueness whilst being permanently networked to everybody else’s lives. Not for them the void or solitude, but the illusion of 24/7 togetherness.

The response to this generation however, is probably not to fully digitise everything. This debate began in the realm of arts education, with the example of learning via MOOCs (Massive Online Open Courses) where somebody in Egypt can download an educational package from MIT (for example) and thereby undertake an educational pathway without leaving their bedroom.

The statistic given was that out of 10,000 people downloading a MOOC, around 2% follow through with the course: those that do crave and follow-up the one-to-one ‘analogue’ contact with another human being (a lecturer/professor) but for the others, there’s not enough incentive to keep going. There’s nobody else there, so to whom are you accountable?

On occasion I see this reflected in Higher Education in the UK but in an analogue environment via students. There’s a ‘click, buy, receive’ mentality – an instantaneous gratification in making a purchase, and then a frustration when that investment appears not to be providing the advertised product (their education).

This is a great example of a digital sensibility towards acquisition conflicting with a particular philosophy of pedagogy: education is not a thing that you buy.

Education, I’d suggest, is a process of acquiring and developing mindsets: of perceptions and creative and analytical capacities that result in a unique heightened ability for the student to apprehend the world around them. That cannot be evidenced in an instantaneous way (which is also why the reliance on end-of-module National Student Surveys for teaching quality is a total joke, but that’s for another day).

Anyway – back to the theatre’s upcoming generation of makers and their audiences.

Remember that ‘void’ (not a void) in traditional theatre? Boy, is it unpopular in Generation Y. I heard it again in an afternoon session too – it’s boring, it’s not involving enough, it’s limiting, nobody wants to do it anymore, you’re far away from the event, you want to get involved and explore the possibilities.

This polyvocal, plurally-minded and constantly-connected community went on to speak of the work they were making, which was often couched alongside its marketing – or rather (another death), around the end of marketing and the birth of early participation, whereby the beginning of the narrative experience occurs via digital platforms.

Spectators and hopefully new audiences become activated via these platforms, engaging, co-creating, choosing and acting alongside the show’s narrative before the ‘live’ experience begins. It’s free, democratic, cheap at source and builds a new community for the live work and the company.

So there’s a political intention here too, totally laudable, around accessibility and visibility – using social media to begin a creative/artistic experience that might reach beyond a traditional catchment of audience members, and introduce new blood to the live event.

What was also discussed at length was the idea of inhabiting dual or multiple worlds, and how a spectator can live at once in a real and digital world in this build-up or within the performance event itself – a duality that’s been a phenomenon of theatre since the Greeks, when we’re always in the presence of that actor-character conceit. Now thanks to the digital realm we can occupy it ourselves.

But – and here’s the big but for me – when did we have to start performing this doubling as spectator to therefore better engage with the artistic creation?

There was a latent assumption within the discussion that made me wary: this valorisation of participation, which I’d agree is absolutely part of the digital world and our socio-cultural existence as we continually make and re-make our identities via social media, or partake in first-person video game sagas – but it’s a habit which seems to increasingly be part of theatrical storytelling, without necessarily asking why it’s artistically preferable.

This led on to the concept of solely ‘user-generated’ theatre – audiences being totally in control of a narrative, which was balked at hugely by one panel member. It was then more helpfully unpicked in a dramaturgical sense.

The schema that underpins digital participatory performance is still largely set by the makers – the architecture is not necessarily fluid or adaptable: it’s fixed and limited, and only ring-fences the spectator in a hall of mirrors. There’s no real choice, no real ownership – the authenticity of autonomy is flawed. We think we’re independent, but it comes with limits.

This led on to an observation from cultural theory: that as consumers of theatre we’ve gone through post-modernism (destroy all grand narratives, show the artifice) into the post-dramatic (narrative no longer competently expresses our world) and, now floundering, are reaching back to the digital because it is a sustained alternate reality. Paradoxically it’s something concrete we can rely on – we want to believe in something unreal again, but that something needs to also be in conversation with the world around us.

The discussion begin to wind down with the youngest member of the panel (22) commenting that her generation of makers really struggled with focus: too many choices, not enough specializing in craft, too much running from one thing to another, or the implementation of digital technology when it simply wasn’t required.

She gave the example of a business that was launching marketing streams on Facebook, Vimeo, Twitter, Linked In and Instagram, when the latter was wholly inappropriate: their business had no interesting visual presence at all – so why even go there?

I reared my head up as playwright at this point and said I felt similarly about my own craft – why are we going there with the digital, with participation, with multiple storytelling platforms: is it driven by artistic need, or is the tail just wagging the dog?

As another delegate pointedly mentioned at the end, most of the Generation Y that he works with come together to make live theatre because they’re already perpetually immersed in the performance of their lives via multiple digital platforms. What they really respond to is getting together in a room in real time and space and experiencing the alternative – not replicating it via the theatre they make.

It came down to a question of appropriate application – the digital playground is full of tantalising equipment, but the artistic need should perhaps be brought centre stage more frequently. Then again, that may just be a blinkered comment from a Generation X single-minded vertical thinker, not a Generation Y plural-minded horizontal thinker.

Maybe we’re not as far off from a digital theatre backlash than we think: a movement that might seek to protect the theatre as a place of the ‘biologically’ real not just the new ‘digitally’ real. Some companies seem able to do both. Perhaps that’s the future. But as somebody commented during the panel:

‘We can try and formulate answers about what’s going to happen in the future – but there’s no truth in that’

The truth is that the theatre of the future is being made by all generations right now – how they might best speak with each other, whilst also maintaining their differences and not ostracising one another, is the challenge.