(Schwalbe Cheats: image from brakkegrond.nl/en/agenda/ietm-schwalbe)

I’m thirteen years old.

It’s dusk and the lights are on in a dilapidated scout hut down a broken pathway in a rural village, where everybody else is doing the flag down ceremony: a mark of respect to the pack, the Queen and God.

Meanwhile the limbs of my friend and I are knotted, twisting around themselves on a patch of scrubland as we roll on the floor fighting, dimly lit by the scout hut.

Well – we’re not actually fighting. Sort of… wrestling. With palm slaps. We’re working pretty hard, you can hear it.

Then again, we’re not really going to hurt each other because – well, that’s just the agreement. We’re friends. We’ve also got this toxic relationship that sees us riled, angry and ferociously competitive. But hurt each other… no… we won’t do that… will we?

Schwalbe Cheats takes a group of eight performers and divides them into teams. They come on in underwear, dress themselves from a pile of clothes on stage and then play some games. They don’t tell us the rules, but we work them out pretty quickly. They get increasingly physical in nature, and it’s all in good fun.

Then a new game starts. They have to try and remove one another’s clothes. They chase, they rip, they wrestle. At first it’s a little frustrating and awkward to watch. But you keep watching. You’re compelled to see where it goes. There’s a line here, it’s just a game… isn’t it?

The rules are bent. There are slaps, hits, hair pulling. It’s all real, there in front of us. We don’t step in. We keep watching. One man ends up naked after having had his boxer shorts ripped off from underneath his jeans. We hear him squealing. The audience laughs and winces in nervous complicity.

There is a lighting state that gradually gets dimmer and dimmer. There is no soundtrack other than the sound of breathing, slapping, effort, and feet padding around the flat blue square arena they’ve set up. There’s the occasional call of ‘time out’ or ‘line’ when somebody steps over the playing space. But that’s it.

Eventually three players are blindfolded in various states of undress (once your clothes have started to come off, you’re not allowed to readjust them) and have a play-off.

There’s a winner. They all hold hands and sing a song and then the show’s over.

I think this is what people call ‘contemporary theatre’. Or at least it’s one version of it. It was also at times the coliseum, a sports stadium, an asylum, a political chamber, a street late at night, a wrestling tournament, an exploration of gender, a provocation to the audience as to how far they will allow themselves to be complicit in their desire to keep on watching.

The joy of festivals like these is that your brain is often requested to kick into action when you least expect it. I left the performance to rush to the next, deciding for myself that ‘yeah that was interesting, but I think it would have been better if they’d taken more risks with the rules’.

Then a friendly Canadian choreographer asked me what I thought of the show, and when I told her, I realised what I was asking for was more violence. More dressing-down, more transgression, an actual sense of boundaries crossed, not just flirted with.

This sort of work creates curious questions for an audience post-show – what was the point in that, and where did I find the meaning, why did I keep watching? What’s my role at a live event? What happens when that role is questioned?

I’ve seen plays and story/writer-led work that also toys with that question (see The Author by Tim Crouch), but they tend to be framed with a more developed character narrative alongside these conceptual meta-theatrical wonderings. Here it’s bald and direct. It’s slightly less engaging, more raw, much more stripped down… but I kept watching.

Sometimes art asks you questions rather than tells you a story. This is the habit of a lot of non-performance-based art, and we’re usually more comfortable encountering that dynamic of ‘spectating’ within those contexts – music, sculpture, modern art, installations. Perhaps more rarely in theatre. (NB: I know this is blindingly obvious to some of you who’ve left behind plays as a dusty relic of a forgotten pre-internet age, but it’s easy to get trapped by habits and expectations when you have the word ‘play’ and ‘wright’ in your job title).

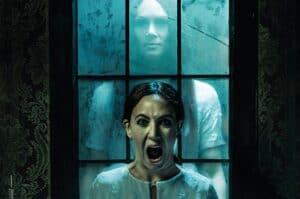

The expectation of being scared out of my wits by Horror was disappointed. A technically (and yes digitally) accomplished production with huge design values, but a total patchwork dramaturgy of popular horror film references, dance, an abundance of illusory stagecraft and a very loose narrative stitching it together which felt more like an afterthought.

Horror aficionados with whom I’ve spoken to since have bemoaned the big gaff: most horror is frightening because you’re sharing a sense of psychological fear or jeopardy with the characters and here, there was none. Lots of theatre magic though, and lots of fun. To a horror lay-person, it was an entertaining bit of self-referential theatre spectacle. Those expecting a layer beneath that were more jaded.

And on to today – I’ve just spent this morning in a session called Generation to Generation: New Theatre Forms for New Audiences. The content and debate was vast and rich, touching on education, young people, philosophy, performance, social media and marketing.

It’s going to be another blog altogether, but after a two-hour debate the question posed at the end of the session was perhaps the most useful, reminding us that opportunity is not actually the same as necessity:

Do these new audiences and new generations coming up behind us necessarily need new forms, or is analogue theatre – the live, real and tangible – their new alternative from a life dominated by technology?