This blog was first published in Summer 2016.

I’m now almost at the end of my Arts Council England and Peggy Ramsay Foundation-funded Protected Time to Write project. This is blog 9 in a series of 10 tracking a playwright’s process from initial ideas to first draft, in a bid to share some of the learning that’s coming out of it.

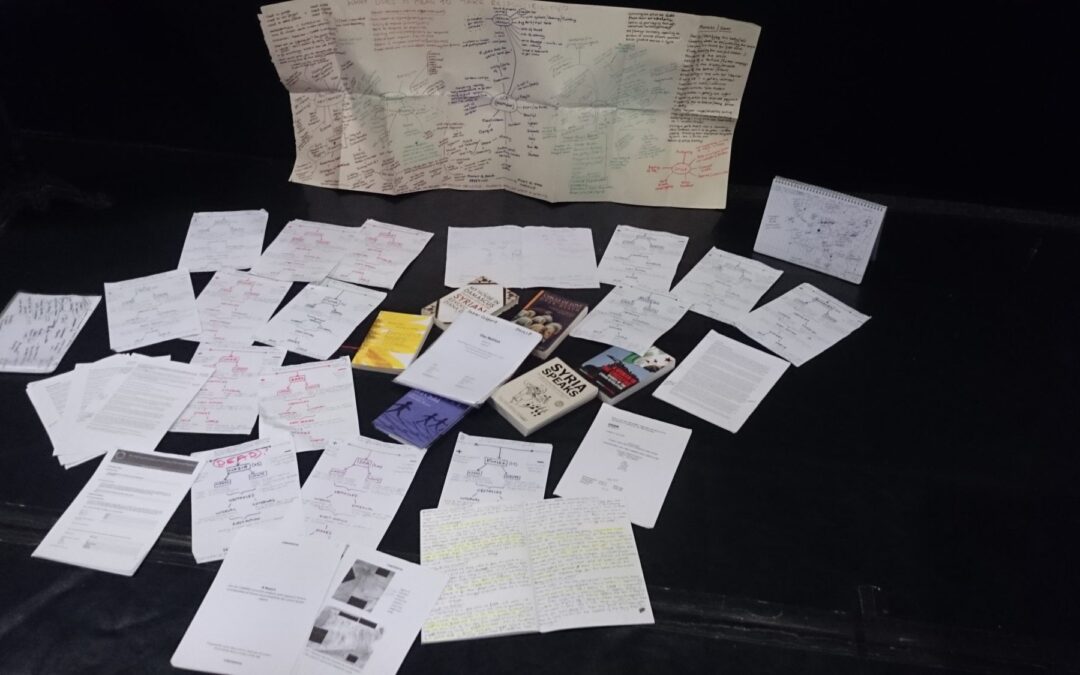

(what one playwriting process in paper form looks like)

Many aeons ago, you may remember I was writing a series of blogs to accompany an ACE-funded writing period supported by the Bristol Old Vic and Peggy Ramsay Foundation. There were to be ten blogs that tracked a writer’s journey from process to play.

After blog number eight in July 2015, which reflected on my witnessing what I considered to be the ‘rough draft’ of my play seriously nose-diving in front of many respected professional others, it all went quiet. Why?

I couldn’t answer this question properly until about nine months later (or rather six weeks ago), when a director friend of mine pointed out that I was continuously avoiding the writing of the next draft and, seeing my pained expression (not for the first time), just suggested ‘you wrote the first draft, even if you called it something else – maybe it’s time to put the play away until you need to write it?’.

My writing time (in terms of money, and that equalled time) had run out back in July, and I’d extended the project deadline once, twice, three times since then whilst I was back juggling other multiple projects, childcare and so on.

But it wasn’t so much all that, as the fact that she was right. I’d fallen out of love with the play – and if there’s one thing that’s bound to sour the want to write, it’s feeling like you’re having to fulfil the writing of something rather than needing to.

More importantly however, this suggestion helped me to identify something else.

When I looked back at the criteria for success that I’d set myself for the project in the ACE application, I realised that despite not having written the play that launched the next stage of my career – and on top of that, said play also diverting far away from the ‘voice’ I was trying to develop as a result of the project – I had in fact achieved what I’d set out to do.

As a result of over-processing, desiring to be a playwright I wasn’t, setting unfeasibly high expectations, trying to serve a ‘marketplace’ of new writing, vanity, pressure, a panic that what I was doing before wasn’t ‘real playwriting’ or a strong enough voice in its own right, and a number of other (imagined and real) contextual factors, I’d eventually recognised my greatest strengths as a playwright and grown the self-confidence to be more me and less everything/everyone/everywhere else in my writing.

I’d told the Arts Council that I’d use the project to write a play, and in doing so develop a stronger sense of my process. The broad aims and objectives written within that ACE application – stronger identity as a writer, fuller employment, national/international projects, urgent contemporary plays of political and human interest – are now actually happening, not as a result of the script itself but the learning I’ve undertaken whilst trying – failing – to write it.

All of this was consolidated into an evaluative workshop/reflection I offered to seven writers at the Bristol Old Vic last week, carrying the same title as this blog post.

At the end of sharing this eighteen-month journey, during which I bared everything of my clunky process, self-criticisms, learning, searching and dealing with what felt like at worst ineptitude and fear, and at best a misguided desire to please everyone else, one of the participants said:

‘I recognise absolutely nothing of doing writing from what you’ve shared over the last ninety minutes. There’s plenty about being a writer, but for me there’s nothing I recognise from my own work about just doing the writing.’

Ouch.

This process has made me pretty thick-skinned I have to say, but this was the toughest thing I’ve ever heard said to me as a writer. It felt like an utter negation of 14 years of learning and attempting to teach others.

Many of my most tried-and-tested bits of writing process were in that sharing, and whilst they weren’t all as useful as I’d hoped they’d be in this project, they’re still part of what make up my fundamental conception of playwriting.

The other useful thing I’ve learned however (and finally begun to trust in relation to my own writing), is that all writers are different and – as anybody who’s tried will tell you – you can’t teach playwriting, even if you can offer tools of the craft. The writer I was during this project, and the writer he is, were at polar opposites.

In that split-second of total neurotic fear at being utterly fraudulent, I realised that he was also partly right. This whole project had been de-railed by process: by a need to be something through doing something, rather than just writing a play.

I smiled and found a way into replying in what I hope was a democratic fashion, even though deep inside I felt like I’d just been caught out by the writing police.

But a couple of days later, rather than grating at me the comment seemed to have grounded me even more in a commitment to just get on with doing what I know works: playing to my strengths, staying truthful to my instincts in the act of getting-on-with-the-writing and worrying less about how everybody else sees it.

And in all honesty, blogging about it with an intention to ‘share learning’ was in fact one of the biggest mechanisms I employed for lying to myself about what was actually going on in my heart – and if you’re not truthfully writing from that part of yourself, what’s the point?

In the tenth and final blog in a couple of weeks I’ll draw out some more specifics from the whole process, but for now, I’ll leave you with what’s been generated: I call them my ‘myth-busters’.

I was going to write that ‘I wish these had been said to me before the process’ but in fact, if they had – I probably wouldn’t have believed them. Sometimes, you have to fail to win.

Top 10 Myth-Busters (or, things I don’t think about my process anymore)

1. That there is a type of writer that you should be like: be more like you

2. There is a sort of process you should be engaging with or you’re not a proper writer: your process is whatever serves and guides the particular project you’re making

3. That you should have a fixed process and know it before you begin: keep your process open to change

4. That you should be walking around with loads of ideas in your head about the world that you’re burning to get down on paper: every writer’s rhythm and motivation is different

5. There’s a particular career and financial trajectory that makes you a proper, grown-up, professional writer: what makes you a proper writer is telling your truth about the world

6. Setting yourself stratospheric ambitions based on established models of what success looks like will make you a better writer: no, it will only make you feel you can’t live up to it

7. Blogging about process and sharing it is a great way to assess your ideas and progress: but not if you use it to disguise the truth of what you’re actually feeling so that you don’t look stupid

8. That you are beholden to the submitted structure of your activity to ACE: you’re not, they’re not the boss of you, the idea is

9. You’ll feel more like a writer if you’re writing plays like the ones over there: no, write the plays inside over here, in you

10. That there’s a marketplace you should be guiding your writing towards: let the marketplace come to you if it wants, and in the meantime just make sure you don’t starve

In other words…

Value your strengths: master better what you are, not what you aren’t

Listen to your gut and your heart: learn to separate difficult writing from untruthful writing

Don’t strain to ‘be political’: any human truth you feel you’re expressing will be a political act anyway

That writer out there you think you should be:

is YOU.