Unreliability of narrative creates a space for audiences to wonder.

From whose perspective is the action before us being presented? Is the scaffold of this story fixed or mutable? Is the world that contains that scaffold consistent? Is the theatrical frame itself playing a game with us, through which we come to understand a human experience more deeply? Are there, in fact, multiple worlds and possibilities being conjured up?

Ambiguity in story, I’m often telling playwrights, is a useful tool for piquing the audience’s desire for judgement.

Without an opportunity to judge, we find it hard to form a relationship with characters – we think they’re good, bad, right, wrong, problematic, confused… perhaps we want to know why they’re like that, why they’re taking these actions, why they’re treating other people in a particular way. We seek to understand and in doing we see we arrive at empathy.

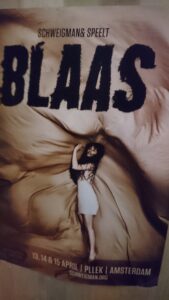

For somebody who trades in words – they’re what I use to think, organise, communicate, instruct, tell and design stories and structures – it was a satisfying experience to encounter two dance pieces last night that took ambiguity and unreliability – not just of narrative, but of world, character, space and audience role – whilst also placing them at the core of their dramaturgies, and almost all without words. In the case of Blaas, for 90% of the show it was also without human performers even being visible.

In dance piece How Did I Die the question contained in the title forms the pivot for multiple orientations of evidence. A girl is murdered in the woods by a man. Why? How? Who knew?

Two female friends and a male acquaintance – who is variously a boyfriend, a friend, a stalker, possibly a completely new acquaintance – play out the different permutations of events leading up to and following the murder.

Occasionally he is murdered. Occasionally someone else is, and the perpetrators switch and shift. They track backwards (literally) through the space, moving jaggedly and awkwardly like an analogue video on rewind, demonstrating what has happened in the build up to an event – but then in playing it forward again in linear time, there are subtle differentiations.

The past is presented and contradicted, made and remade, moving backwards and forwards until different versions are colliding and spiralling off somewhere new. Fact and fantasy collide, the truth is slippery and events are malleable. It can appear repetitive, and the lack of a final clear narrative spine that ties it all together may frustrate some, but I felt that was the intention – how can we be certain of an incomplete picture?

Twice in the piece we revisit a single elongated section of text, where the original victim’s friend is recounting her panic whilst offering a statement to police. We understand from her that there is a man she knows, who has killed somebody, but we don’t know exactly who or when and even she has been confused by police interrogation about exactly what she meant, having had her words twisted out of shape. She now questions her own memory. In this world, even lived experience is rendered unreliable.

I’d have loved to see the piece a few more times, to draw out the structural map of this work to comprehend better all the narrative permutations: but in the live moment, that’s part of the challenge for the audience.

To borrow an example model of the gamer’s role from this morning’s session on The Performative Playfulness of Storytelling, we’re working out the rules of this dance world as they unfold before us. We’re complicit partners – players, even – in a pre-designed game of truth and lies, offered evidence as a puzzle and repeatedly attempting to put into motion a chain of causality via:

action – something has happened to lead to this murder

reflection – is that the truth? is what we see what we get, or something different?

hypothesis – I think I know what’s happened here – do I?

verification – now I understand what’s happened

The piece trades on the first three, but leaves absent the fourth. Depending on your need as an audience member, this is either a lasting intrigue to take with you on a wander through the rainy streets of Amsterdam – or just a huge cop-out. I’ve certainly heard both points of view. I still think it was complex storytelling, without words, but with a stark and clear story question at its core that is deliberately left unsatisfied.

Blaas is the first piece of theatre I’ve been to where they give you plastic over-shoes to wear. At the back of a long warehouse, padded with a white plastic floor and surrounded on all sides by strips of LED lights, we sit and wait, until a pile of parachute silk at one end of the room, crumpled into a long heap, gently, gradually, begins to fall and rise.

It takes on many forms until it becomes a 3D almost-cube – the corner nosing into the audience, searching, sniffing, asking us to touch or interact maybe… at times it appears scared, fearful, excited then curious… at other times we’re not interpreting emotions, simply spellbound by the grace and quality of its movement, a ballet of shapes and light.

I won’t reveal what happens next lest you choose to go and see it, but it’s an unexpected transformation: an all-encompassing theatrical coup that sees you transported inside the world of this living art-sculpture-installation, building associations in your imagination from a semiotics of light, space, air and sound.

It’s a shared experience, perplexing and at times even meditative. I’ve not felt like I’ve been inside a modern art gallery very often when I’ve been to the theatre – but here, I felt encouraged to let go of my narrative expectations altogether, and asked to piece together an abstract experience where we become – temporarily – the abstracted art itself.

Touching briefly on my core IETM attendance question from my first blog – how might all this be relevant to the very basic aspects of crafting text and stories for performance? – I feel from both of these shows that entertaining a sense of plurality, puzzle and openness within my playwriting might put the audience in a more intrigued position.

I’m reminded of plays like Fin Kennedy’s How To Disappear Completely and Never Be Found, where the protagonist is both alive and dead at the same time, or the work of American playwright Mac Wellman, where worlds are fluid not fixed, characters confounding expectations by carrying multiple identities of both real and fantasy worlds – or structures like Martin Crimp’s Attempts on Her Life, Fewer Emergencies or Nick Payne’s Constellations.

It’s a great challenge – to tell stories where the play’s structures are playful, or playing, even dancing, with their audiences’ imaginations, without them having to become active physical participants in the action.

As a delegate commented in this morning’s session on The Performative Playfulness of Storytelling, if you provide a gamer/player/audience with everything they need in front of them, what work has the imagination got to do?

Imagination – the brand new old immersive experience that we should try and remember.