This post originally appeared on the Lane’s List in January 2015.

I’m continuing with a recent child-inspired line of enquiry by following a more lateral pondering about playwriting process – or more precisely, how freely we allow our imaginations to operate.

I met up with the brilliant 5x5x5 recently: an incredible organisation jointly reinventing schools, teachers and children’s approaches to what creative learning is, and how it should operate as an equally valuable part of the curriculum to literacy and numeracy.

They run the fantastically innovative (and – if you’re an artist working within it and attempting to co-navigate into unchartered waters yours, the children’s and their teachers notions of what school is for – fantastically challenging) School Without Walls project. They’re also looking into creating a House of Imagination in Bath – a permanent venue for artists and children to work together. You can see more in the short film here.

What’s great about meetings with 5x5x5 as an artist is that you feel a little bit like an eager child. They keep asking you how you want to grow. What do you want to explore in your own practice? How do you want to develop? Why and how might engaging with children’s creativity help shape those aims? What are the questions you don’t have the answers for that excite you, and that you might want to explore alongside children?

We met up in the Victoria Art Gallery where a contemporary sculptor was co-facilitating a drawing session with a reception class (4 – 5 year-olds) who were creating their own work in response to her exhibition.

I watched them receiving with unbridled excitement and joy an invitation to draw their own pictures in response to the sculptures (no instruction to copy, mimic, or echo, importantly). I then went for my meeting. When I was asked how I wanted to develop my practice at the moment, I simply said ‘As often as possible I want to feel like that when I’m in a creative process.’

One of my favourite TED talks of all time is by Sir Ken Robinson – viewed millions of times by others on YouTube – about How Schools Kill Creativity, and how children are natural creative artists because they’re not afraid of being wrong: and that if we’re not afraid to be wrong as adults, how can we ever hope to come up with a shred of anything original?

Along with the moment above in the Art Gallery, I was reminded of another conversation last year with Kaleider where – after four sessions of five with a Year 6 group, creating content for a book of stories about the Age of Oil – I was beside myself with panic about what the sessions had achieved, how it hadn’t felt targeted and specific enough, why I didn’t feel I knew enough about the bigger picture of the project and blah blah blah blah and the word that was thrown back at me by the staff at Kaleider was ‘adumbration’ – one with several meanings but the important one being ‘to foreshadow; prefigure’. To trust that something is coming before it arrives.

The children weren’t worried about what they were doing. They were just doing it. So were the reception class in the Victoria Art Gallery. So is my daughter when she squeezes playdough or splashes about with paintbrushes and water. And actually, so was I when I started writing seventeen years ago. I didn’t have a developed inner critic because I hadn’t learned the rules yet about what was right and wrong. More you learn, less you know. And when you need to put to one side what you know, you simply step into the void and trust that eventually, something will reveal itself.

How often do we feel like those children in our process? How difficult is it to really occupy that freedom of mental, physical, and spiritual movement in our whole beings that results in unbridled creativity? This is why people go on retreats, I think, or do the morning pages routine (the latter of which I’ve never tried, but wonder if perhaps I should).

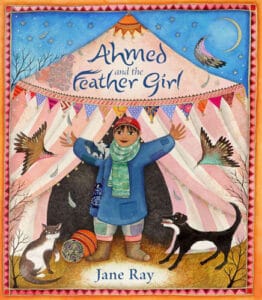

My daughter received a children’s story this Christmas called Ahmed and the Feather Girl, about a young boy Ahmed who lives and works in a travelling circus and finds a golden egg in the woods. He brings it back to the circus and places it on a nest of willow twigs to keep it safe, and in the spring it hatches a beautiful young girl who sings like a songbird.

She is caged by the elderly circus owner who then earns her fortune from displaying her to the public: every morning as the sun comes up the girl sings and sings, but as spring turns to summer she hears the wild birds in the forest and grows sad. She stops singing and Ahmed, feeling the pain of her incarceration, sets her free.

He is severely punished for his actions but, over time, is visited in his dreams by the girl and wakes every morning with a feather in his hand. When the winter months descend, one night he hears a beautiful song on the roof of his caravan. The girl is there, beckoning him, and as the feathers from his dreams form into a beautiful coat, they both lean together into the wind and fly up into the starlit sky, wing-to-wing, to the place beyond the stars.

I cried when I read it. There’s something about the freedom of imagination in the book and the quietly sincere, declared way it reveals its world.

Yes, there are golden eggs. Yes, there are children born who sing like songbirds. Yes, some of them grow feathers. Yes, a dream can be at once a dream and a reality. Yes, a pile of feathers can become a cloak that makes you fly. Yes, there is a place beyond the stars. Yes. Yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes.

Thinking literally about the world we live in is something we perhaps already get from other sources: media, journalism, news. Stories, however, invite us to think laterally – to imagine unreal worlds that can tell us truths about our own, and in doing so, those unreal worlds become more real than we thought ever possible.

If we can encourage our imaginations to occupy that same childlike state, perhaps we’re on our way to becoming innovators of richer fictional worlds; rather than just mouthpieces for the literal one we listlessly chew over, helplessly dramatising what’s already outside the window instead of conjuring up the worlds we used to dream of – the ones that lie just beyond the stars.

Enjoy? You can read more like this every Monday on Lane’s List: a weekly subscriber email that in 2014 distributed over 600 opportunities and industry articles for UK-based playwrights. You can read a sample list or find out more here.