This is the second blog of ten that will appear between now and early July, as a public engagement element of a funded playwriting project supported by Arts Council England and the Peggy Ramsay Foundation.

Blog 2 first appeared in Lane’s List on March 16th 2015. You can read Blog 1 here.

The first week of seven has now elapsed in my Protected Time to Write project: best described as a two-pronged attack on (1) my self-led writing process (it may sound weird to say that, but the last seven years has seen it led by briefs from and contact with young companies, teenage audiences, community and participatory work, rural touring, cast restrictions, adaptation material – all honing my craft but none of it beginning just with me and an idea) and (2) the writing of a new full-length play.

As part of the agreement with the Arts Council for public benefit, I’m writing ten blogs reflecting on the project in the vain hope that some of what I’ve encountered might be useful to pass on to others. And in a strange sort of way, that very need to communicate has characterised some of the most useful moments of my process in the past week – not being in a room on my own, but reaching out to others, requiring me to articulate clearly what the hell it is I think I’m actually doing.

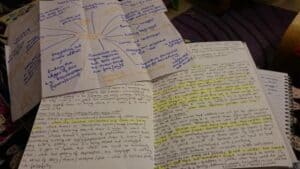

But that all came later: I began on the first day with a set of questions about me, the play I was writing, and a couple of lists and exercises from other practitioners too, some of which I shared in Blog 1 (soon to be available on my website).

This all felt terribly indulgent and not-like-really-writing-more-like-procrastination-and-navel-gazing but in truth, it pushed me ahead.

Loads of my questions were ones about permissions (though I didn’t realise this until looking back on them). Permission to write a certain way, permission to hold onto aspects of my process I didn’t want to drop, permission to divert from the working structure I sent ACE to help generate the funds, permission to go back to square one with the idea I’d been grappling with back in November despite having taken it three days into a different direction already… sometimes all we need is to let ourselves just say YES THAT’S OKAY and crack on with it.

Part of identifying what it is we need permission for, however, is a good step towards discovering our identity as writers. Most of the things I wanted permission for betrayed my worries and insecurities, my false leads (trying to second guess audiences and venues, trying to please anybody but myself with what I was doing) but also my strengths.

The long list of questions about my play idea was great for usefully exposing the knowledge gaps and showing me what I most needed to tackle first. Some of them were about form, most of them were about content, but they ranged from the very specific:

Does this character need to have some aspects of a Syrian accent if she’s been born outside the country but has lived there for seven years, and how do I weave that in?

To the much more general:

What’s the human experience I’m actually interested in or trying to understand for myself?

Or:

Where is it set?

Other exercises included imagining how other playwrights I really respected might approach my idea, just to loosen up my own expectations and try and not to get stuck too early in making choices.

I’ve imagined my idea variously as a play by David Harrower, Tim Crouch, Martin Crimp, Howard Barker, Philip Ridley, Sarah Ruhl, Kaite O’Reilly, Will Eno and Martin McDonagh. Surprisingly this didn’t end up in a personality crisis but in a whole new set of ways that I might express the content that’s pulling me in, and given me some new emphasis on areas that were in my blind spot.

I looked at motivational lists of questions from Kaite O’Reilly on the Purpose Behind Our Writing and Katherine Mitchell on Writing Without Self-Censoring and (again) gave myself permission to spend a few hours on the answers; looked back through a huge file of interesting articles and interviews I’d never had time to read (including this fiendishly challenging but – if you give it the headspace it deserves, hugely rewarding – blog about American playwright Mac Wellman’s dramaturgy); I did an exercise my mentor at Theatre Bristol suggested about writing down how I wanted to feel about myself at the end of this project and being as egotistical and uncensored as I could possibly manage… and then my ideas started feeling lonely.

The trouble with such a huge chunk of my writing career being responsive is that I’m very, very used to conversation. Suddenly I got what ‘being on my own’ meant – I was taking it too literally. I want to be on my own more to be in control of my own ideas and process than to be a totally solitary writer up in an ivory tower somewhere. There’s no point in denying yourself what you need for the sake of honouring funding phraseology.

So I picked up on another piece of advice and set myself a series of artist dates. I emailed twelve people who I’d worked with before, or whose work I knew and admired, and invited them for coffee and cake and 45mins of chat about what I was doing, in return for 45mins of my own time at an unspecified point in the future. I set no big agenda. I’m not planning these meetings. I’m talking, seeing what falls out of my mouth and waiting to see what happens.

People can come if they want, or not. If they don’t, I’ll spend 45mins imagining what they might have said (and eat their cake).

In the first of these (the second is yet to happen) it was glorious: suddenly somebody was talking my idea back to me in a way I’d never understood it before. They were simply sharing anecdotes and examples and chatting about their own approach (the first was an actress) and it was illuminating. None of them are dramaturgs by name, but it’s fantastic dramaturgy. And I found things coming out of my mouth that I’d never heard before, that were clearer and more decisive than anything I’d yet written on the page.

This need to articulate intention continued when I started reaching out to various organisations via email regarding research: having to describe what I was doing meant having to decide to some extent what it really was – in turn that moved my ideas forward by shaping them in a different way, particularly as most of these organisations are nothing to do with theatre and I couldn’t get away with any lazy waffle.

So what have I learned here that’s useful to share? Obviously I’ve learnt loads about my own writing and the play I’m working on, but that’s not much use to you. But I’ll give it a go:

1. Don’t deny aspects of your process that work: just try and approach them with a new edge

2. SWITCH YOUR PHONE OFF

3. Imagine you’re the writer you emulate most, and how your play might look as a result

Embrace the unknown, particularly in conversation: find people with whom you can trust feeling lost, wayward and directionless

4. SWITCH YOUR PHONE OFF

5. Check out all the links I’ve listed above and then do what they say – you won’t regret it

6. SWITCH YOUR PHONE OFF

There’s another five days to go in my ‘early stages’ section of work, and the focus is now on moving away from me and my process and identity as a writer, and into some big content questions. I’ve also spent three of the last five days reading four books, ranging from bereavement to radical Middle Eastern art. Those questions (a selection)?

What is the nature of grief in extreme political situations like civil war?

What stories do you tell yourself to get through the death of a child?

Why does Syria look different on the outside than the inside?

What do you do if you believe your own president has murdered your toddler?

Can a woman completely recreate her life narrative and the narrative of her country simply by freezing her grief?

Do any of us ever hear the truths about our government, or are we all living in a never-ending spiral of constructed fiction?

For the first time since November, I’m looking forward to trying to answer them.