This extended blog is a reflection on the intersection of archives, history-making and playwriting. Last week I attended Opening Up The Archives alongside academics and archivists at Exeter University’s Digital Humanities Laboratories. We collectively explored the archive at the site before considering its potential for creative interventions.

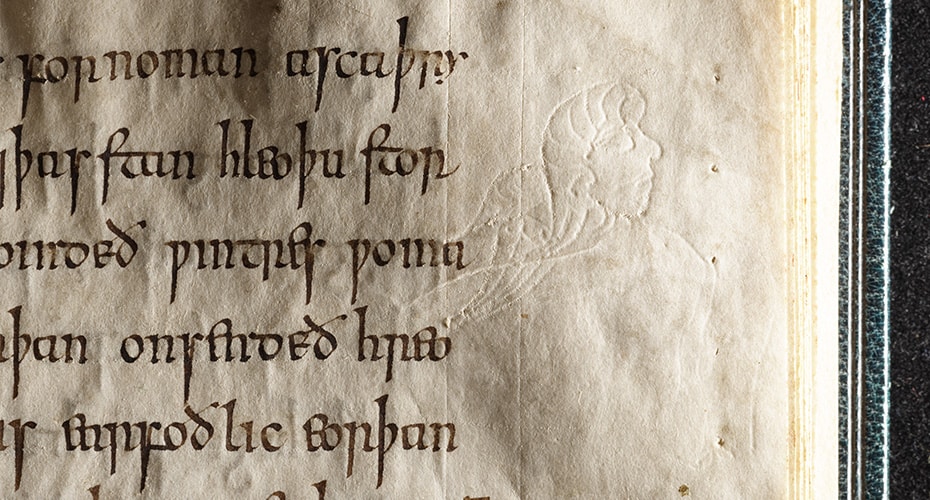

(Image Above from The Exeter Book: a drypoint illustration in the margin of folio 78 [recto] – Sourced Online)

Beginnings

I first set foot inside an archive during a playwriting residency involving the globally-renowned Theatre Collection at Bristol University a couple of years ago.

I held conversations with archivists, historians, librarians, archive volunteers, funding staff and academics. As with most of my writing projects, I went in with a wide-angle lens to discover as much as possible in a realm about which I knew relatively little.

What were archives? What were they perceived to be? When did they begin and what did they have to do with politics and power? What were the promises and secrets of their hidden contents for historians, and what did it mean for those contents to then only come to life when subjectively interpreted? What was the tension between the past and history?

There were also contemporary problems – what did it mean to create simulations of ‘hard copy’ originals via the digital archive, increasing accessibility but via simulacra rather than the ‘real thing’? Did that matter? Should it? Who chose what got archived anyway – and what got left out?

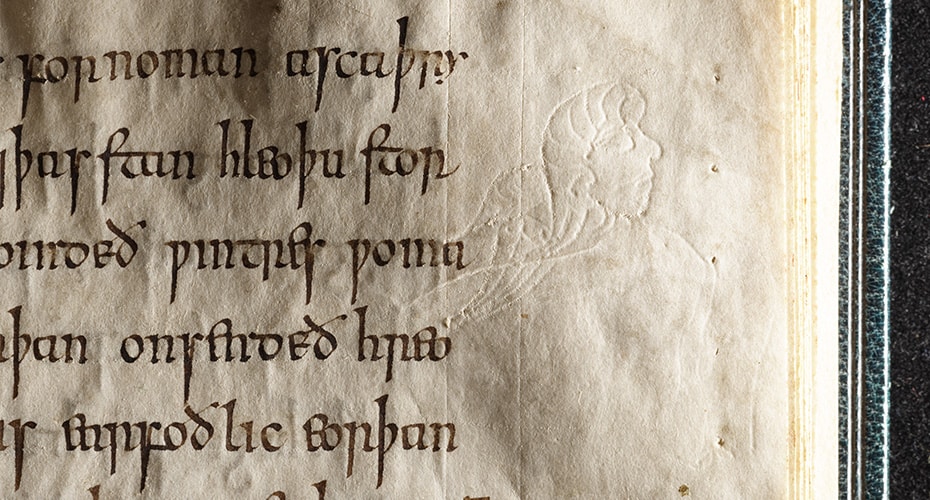

(The eye of a puppet I encountered in the Theatre Collection, which became central to the play)

Origins Unknown, the play that emerged from that residency, was an investigation of human beings’ insatiable appetite for the origins of things.

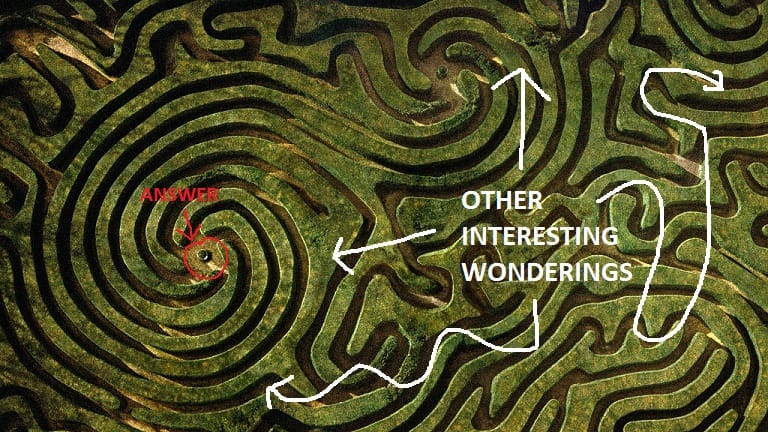

A time-bending structural puzzle, it took the dramatic action beyond linear chronos time into kairos time – a lapse or moment of indeterminate time, or supreme moment in which everything happens.

It wove together a woman losing seven years of her history, the Greek Muse of History Clio, a demonic puppet (based on an object I found in the archive) and a historian who falls obsessively in love with an object from the archive, as a short-term crutch for her grief following her husband’s death.

It was structurally ambitious, contradictory, labyrinthine and unresolved, great fun to write and had archive written all over it.

History Writing and Theatre Writing

What I realised more than anything during my creative research in the archive – and it’s probably obvious to any historians reading this – was how much creativity was involved in history-writing.

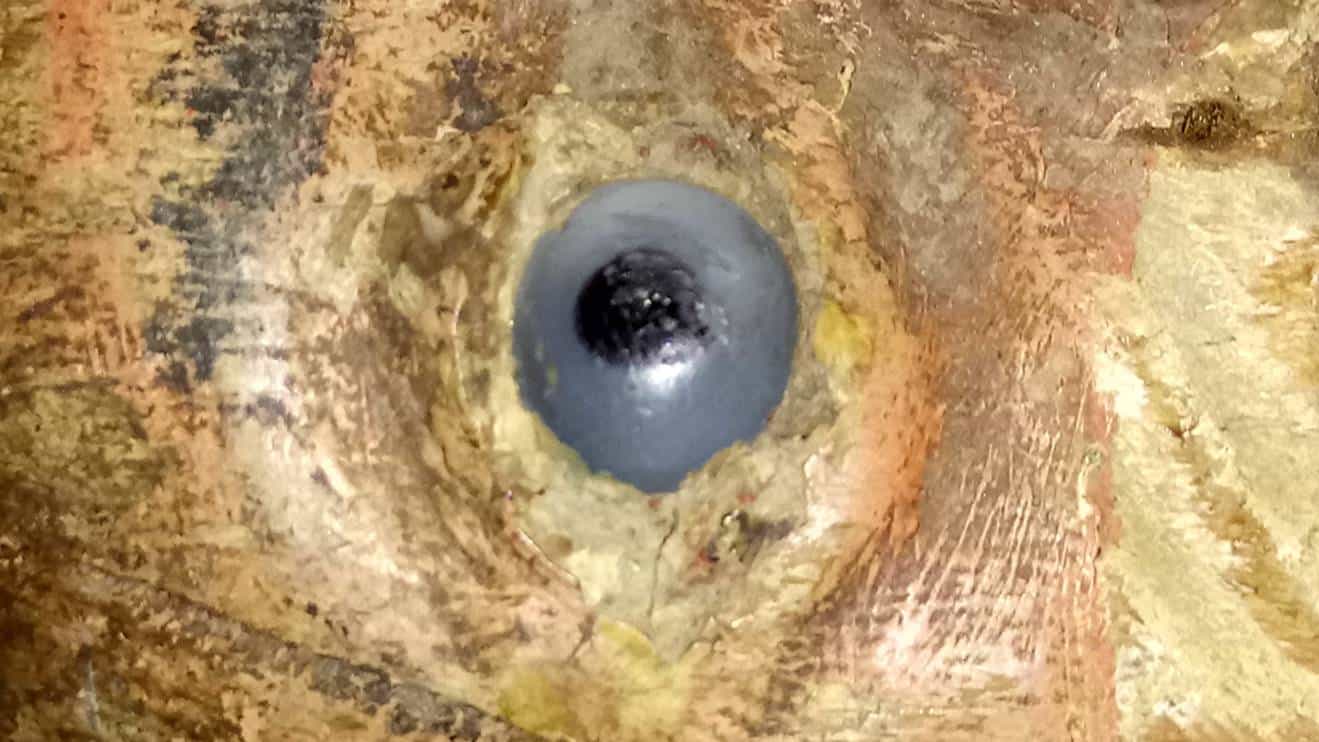

I got geekily giddy over the theory and philosophy of history-writing, lapping up critiques like Carolyn Steedman’s Dust: how subjective everything was, how tied up with the ideology of the interpreter, how it was so much about the story the historian wanted to tell, or how the histories they constructed would always betray some form of autobiographical interest – a re-making and re-envisioning of the past but only in their own image.

This assemblage of evidence, glued together by an imaginative cause-and-effect correlation, to arrive at a conclusion or a sense of ‘what happened’ is not unfamiliar. It’s what audiences do with good plays: ones where the gaps are left for us to intuit and wonder and connect.

It’s also what I as a writer do as I develop my own research (creative, experiential and factual), searching for the connectivity that lies within, and finding it sometimes through structural shapes, sometimes through metaphor, sometimes through story: but always through invention – exploring the gaps and pushing at the edges.

The ‘evidence’ in the archive – as it’s later coined in a workshop led by cultural historian Jeanie Sinclair – is only the bones that once held flesh: not the past but its remains.

Historians are Dr Frankensteins, obsessively reanimating the dead, injecting with a sense of living narrative an assemblage of that which has actually long passed.

‘The preserved only has life breathed into it at the moment of transformation. We seek out the past not to confirm and replicate it, but to author it. At an extreme level, in choosing to archive objects from history, human beings are simultaneously constructing one history that will never be seen, and another that they can never hope to know. The archive – as I’ve come to learn – contains everything and nothing at the same time.’

I was completely hooked. That and the excerpt above (from an early blog on the Bristol residency) was almost two years ago.

For me, excellent drama is built on complex contradictions. I loved the archive for its promise and its betrayal, its preservation and decay, its stories and its silences.

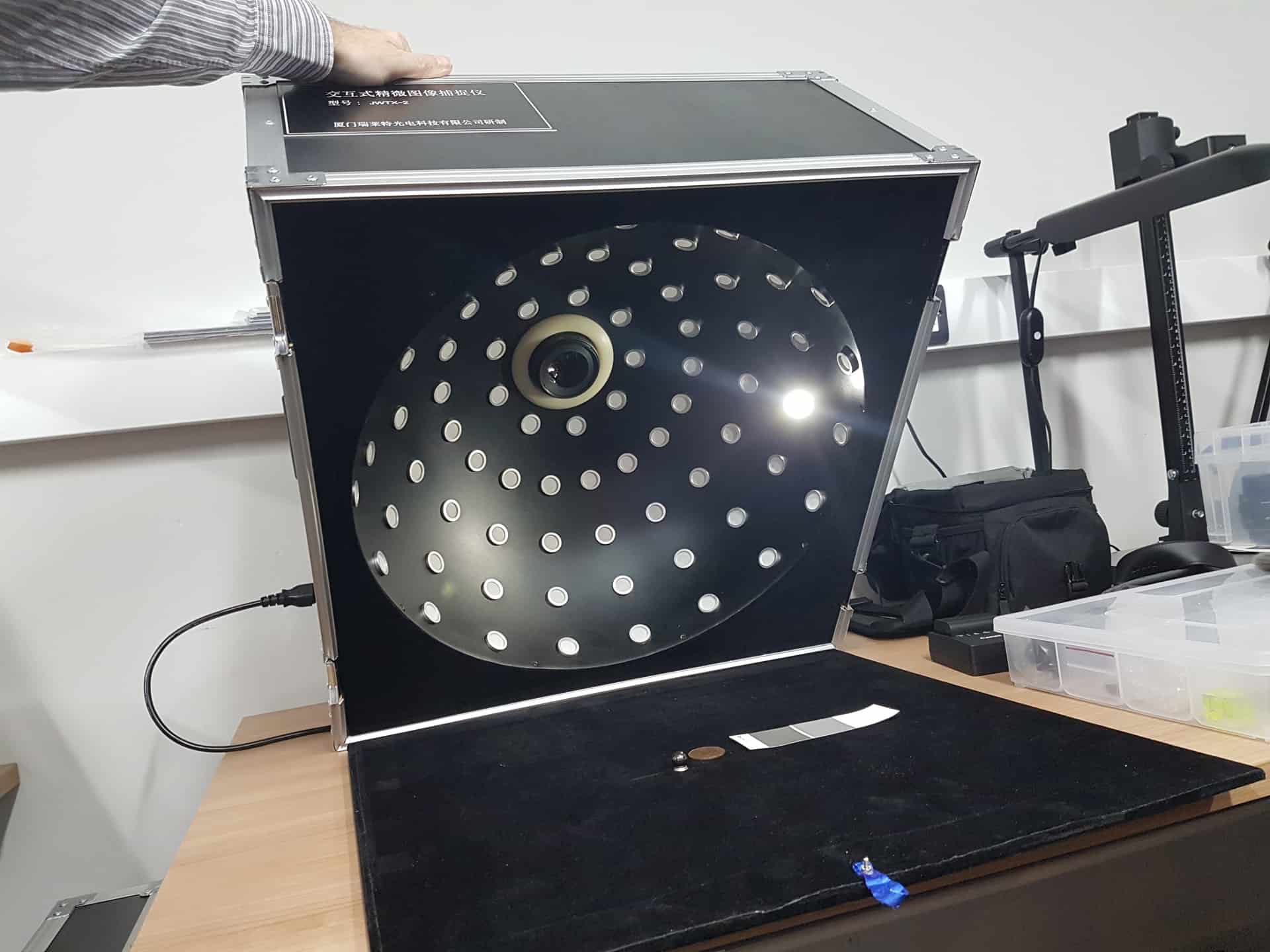

(Not a crime scene, but one of the digital photography processes at work on a fragment of pottery in the DH Lab)

It was therefore a joy to return to this realm at the Digital Humanities Lab in Exeter – a completely different archive – but to find the core questions that nagged me about history-making in relation to the archive not only present, but more compelling than before. In part that’s thanks to the rise of digital preservation techniques.

What follows are some reflections from the day in Exeter that continue some of the thoughts and questions above, but also seek to consider how they’re transformed or complicated by the digital ‘surrogates’ being created in this Lab.

(The Exeter Digital Humanities Lab and Special Collections Building)

Familiar Friends

Several of the images of archive holdings, rolling on the welcome screen in the seminar room at Exeter, honoured an archive feature rearing its head in the news only the previous day.

That was the discovery of Bram Stoker’s original mark-ups on books he’d borrowed from the London Library to research Dracula, now shot up in value due to the evidence they hold of the origins of his research in the margins (his handwriting was appalling, by the way).

The trace of a living hand is alluring – evidence again, of the first marks, the first thoughts of a creative mind in conversation with an otherwise inanimate pile of paper and text. It suggests a new and untold story, a sense of wonder, and a fresh puzzle to be solved.

The broader aims of the Digital Humanities Lab and its archive are outlined for us: increasing the transparency of archival practice, the understanding of access to it, changing perceptions of what archives are and removing barriers to access. Then it’s off to the labs themselves to witness archival surrogacy in action.

360° History: Beyond Human

The 3D printing and photographic labs reveal two distinct processes: the ability to create 3D plastic replicas of artefacts, and also to photograph them with macro-lenses to capture a level of textural detail that goes far beyond what the human eye may be able to detect.

The example we’re shown in the 3D lab is of wax votives from Exeter Cathedral and one complete statuette of a woman in a position of prayer. We can also zoom in on and explore from all angles the photographic ‘surrogate’ on a screen.

(Macro photography: each of these little lights revealing another aspect of the tiny coin below)

In the second lab, we’re told how a similar process of photographing coins, maps and pottery fragments in particular qualities of light can reveal detail hidden to the naked eye in a natural light.

Even more remarkably, it’s possible to detect things like paint pigmentations that might sit underneath a surface image: rather like the discoveries of grand masters under discarded canvases. Digital technology however gives you the option of not wrecking the surface canvas in the process and knowing if something’s underneath before you start.

The final 2D photography lab captures hard-copy archive images again with the macro-lens, providing a stunning level of resolution (they’re currently working through the Exeter Northcott’s production and rehearsal archive, so we’re proudly shown the twinkle in Imelda Staunton’s eye during a show from the 70s).

(The 2D photo lab in action)

History, Perception and Human Experience

Writing plays is about finding unique perspectives on the world through content or form (and hopefully both): discovering that which needs communicating about the human experience, and then communicating it in a way that is unexpected and arresting.

These surrogate archival objects took us beyond typical human perception. This is an enhancement of the ‘real’ as experienced in day-to-day encounters with these pieces.

Technology is breaking open a seam of perception that reveals a new story and – to me at least – a curious macro-world of stories that are nascent whispers, like the faint writing indentations left behind by accident, on one document that happened to lay beneath another two hundred years ago.

I’m predisposed to that wide-angle lens view when interrogating new material. Here, I wanted to know what the limitations and extremes were.

What can’t be captured? Will expert human knowledge and semantic understanding ever be supplanted by machines? What would that do to history? What were the best surprises and discoveries these researchers had encountered so far as a result of this new technology?

Meta-Histories for Lunch

Over lunch I seek out a couple of conversations, firstly to find out what’s next – not in the day’s programme, but in digital archiving. Where are we headed in the next twenty years?

Digital Humanities Manager Gary Stringer talks to me about the use of Augmented and Virtual Realities: a sort of complete archival immersion, a living history, to the point where it might be possible to feel the ‘weight’ of an archived object you pick up whilst wearing your AR headset and hand sensors, whilst traversing the digitally re-mastered sites and locations of the ancient world.

(Using technology to capture that which lies below and beneath)

Then there’s the histories hidden within the histories – the potential study of detritus held in the ‘gutters’ of archive books such as skin cells, which might hold their own story at the level of DNA – a nano-history.

The past suddenly feels ready to be colonised by a new breed of digital historian explorers.

As dramatic material, this is a wonderful sort of government conspiracy sci-fi worm-hole world to image one’s self into, where facts and connections in the past become the exclusive property of those who can afford the tech that reveals it.

Representation and Archive Choices

Putting aside the Netflix elevator pitch for a second though, this tech at Exeter is viewed as the antithesis to exclusivity – not in a privileged way, but as a way of increasing access to archives for a global public.

That said, governance, the archive and the politics of what is saved and for whom is still a challenge. Further conversations at lunch around the politics of archives reveal the principle of community archive start-ups: trained and then self-led groups, currently under-represented in ‘the archive’ at large, who are in a much better position to select what to save than academics.

There’s another meaty dramatic premise in that too.

How does a group decide what gets saved, and can the politics of power, taste and subjectivity be effectively circumvented or not? Who’s editing these new archives and what does ‘expert’ opinion and guidance look like? Can you select democratically?

What would happen if somebody was trying to block one form of representation within an under-represented group, and why might they do that? Do we all want to be (and can we be) effectively ‘known’ through the artefacts we leave behind? And as individuals, or communities?

(Professor Leif Isaksen prepares for his presentation, far left)

Journeys or Destinations

This whirl of questions takes me into the day’s final two 30-minute presentations, firstly from Professor Leif Isaksen as he journeys us through his fascinating and admirably obsessive desire to prove the remains (or not) of an old fort, thought to have sat upon a hill near the area of Scotland in which he grew up.

Isaksen is an advocate for the dovetailing of analogue and digital archives, and the need for human imagination to still do the legwork of interpretation to arrive at an answer.

He reminds us that computers and digital cameras and software, however sophisticated, still have no inner life or mind that can ‘know’ or ‘conceptualise’ what a word or image is in the way that humans can (whilst I as playwright sit there thinking ‘but what if they could…?’).

In terms of creative interpretation and artistic inspiration, it’s the presenters themselves that pull me in here as much as their subject matter.

Isaken’s research journey towards evidence and origins is an obsession – he’s magnetic to watch – but I can’t help thinking if it’s sometimes better to wonder than to know? Is the journey of wonderment towards something more exciting than the final finding out? Once you know, what does that mean?

Answers bring finality. I’m always telling my writing students that ‘concluding’ their stories isn’t necessary. Let us keep dreaming around the characters, the scenarios. Don’t leave us hanging awkwardly but do keep things alive somehow.

Some of the best plays I know are ones where the writers are desperately trying to grasp the ungraspable, and the impact of the dramatic action is in the pathos we feel for their characters, these vulnerable humans stumbling towards that which is eternally in darkness.

I think human beings are drawn not to the big answers, but to the big mysteries, the on-going questions that fascinate us principally because we don’t know and probably won’t ever know what’s at the root of them. What happens when you collide that with the act of history-making?

Then the second talk by Dr Charlotte Tupman contains a moment of pure theatre.

Historytelling

She begins to tell us a story, about a couple who helped out a German balloonist near Exeter in the early 1900s and who’d crash-landed in a field during a race.

They’d taken him in for tea, and about six months later, after they’d helped him back to Exeter to get home, the couple received a package. Inside were photographs of the city of Exeter he’d taken from his balloon.

These photographs were passed in an envelope to Tupman recently, along with the story. They are likely to some of the earliest ever photographs of Exeter that show the layout of the city from thousands of feet in the air.

We in that audience in that seminar room are among some of the first people to hear this story re-told.

This narrative of chance incidents animates the images in an extreme and compelling way. I’m not that interested in black and white aerial photographs. But I’m interested in the serendipity of their arrival in this context, in this moment of telling that is beautifully poised by Tupman, by her awareness that these archival photographs are not just items, but a story, and that there is something precious and beautiful in it being re-told.

(Exeter City from the sky – a modern view)

Deciphering the Archive – Bones, Ghosts and Flesh

The final part of the day is a workshop led by Jeanie Sinclair, a cultural historian and self-confessed archive fanatic who has recently collaborated with Bristol-based writer and theatre-maker Tom Marshman, on the acclaimed production A Haunted Existence.

We’re ushered into groups around five or six tables, with one invited artist at each. On the table are handwritten documents. We’re asked to identify the facts held within them (the bones), the gaps and unheard voices / unseen evidence (the ghosts), and then how an artistic project might seek to gift flesh and form back to both.

Initially viewing these documents completely out of context (and my depth) I’m suddenly back in my A-Level history class, like a rabbit in the headlights as those academics around me keenly press on with immediately sifting, deciphering, analysing.

I’m not even really sure what I’m looking at. Help. What’s a fact? How do we know? What is evidence? Argh. (I still have a recurring dream in my late 30s that I’ve not attended any of the lectures and am going to fail the whole thing).

Fortunately, with expert guidance at hand, the documents are contextualised and our quartet around the table begins to get to grips with them (to be honest, they got to grips with them immediately and I played catch-up for a good fifteen minutes).

They’re records from slave traders and plantation owners. Account books and letters, monetisation of human life and health as goods to be economically valued. The absence of slave voices is stark, ghosting through the margins. It’s only when we reach the third task – to put flesh on the bones – that I find my fifth gear.

One of our group has identified a story in one of the letters. It’s of a plantation owner with a son born of a female slave, but whom he thinks light-skinned enough to pass as Caucasian. He writes about arranging his transportation to England (we think) for an education.

This choice crystallises as a dramatic premise instantly. It draws in three distinct voices with three separate identities – the plantation owner, the mother, the boy. The crossing of borders, the privileged route of escape, the plural identity of a boy in-between destinies.

What do they each want? How do they feel about one another? What might the most unexpected arrangement of emotional dynamics be in this trio? What’s at stake for each of them if this unique transaction (within a world of transactions) fails? Can you ask an audience to empathise with the slave owner? Why? How? What are the ethics here?

They draw in the politics, economics and context of the wider archive of slave transactions in a stroke. A drama of three voices, perhaps experienced as interwoven monologues, perhaps experienced site-specifically within and around the archive itself, as live action.

We discuss how a process might pan out between writer and historians, what network of questions would need answering, what evidence would need to be found to support a dramatic exploration that has to entertain every character’s perception of their own actions as the truth and the right thing to do. I stress that dramatic storytelling is about illustration, not judgement – and about revealing questions through the deep human experiences that the archive might suggest but has not yet brought to life.

This workshop journey is only 45 minutes long, but it feels like a big one: going from initial terror and imposter syndrome panic, to triangulating a solid dramatic premise (and key creative and research questions) that could distil a much bigger historical picture, from only a handful of documents and in a minimum of time.

It’s only scratching the surface of much longer and deeper potential collaborations, but it’s exhilarating. It makes sense of the original invitation in a lasting way, at the end of a hugely stimulating day.

This pathway into the sharing of history-making and archival practice, and openness to artistic intervention and intrigue is a great principle to start with for the Digital Humanities Lab and its Special Collections – I’m very curious to see what new routes and roads might follow in the future.

Enjoy this blog? You can get more insights and receive weekly updates on competitions, awards, submission opportunities, jobs, training and workshops by signing up to Lane’s List – every Thursday, 50 weeks a year, to your inbox.