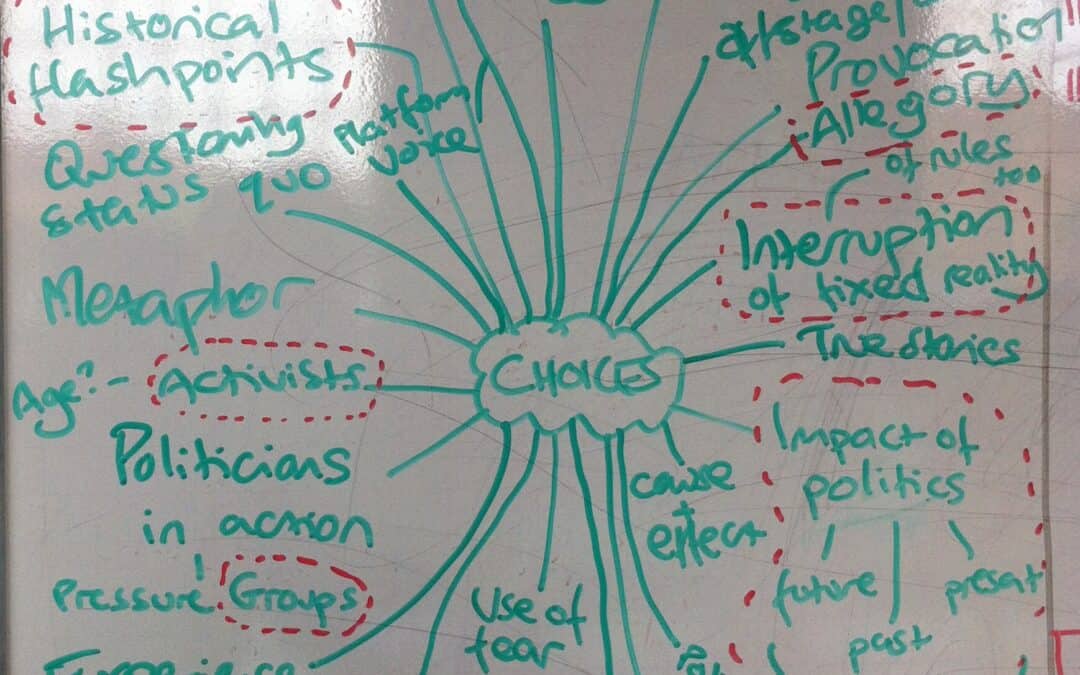

(an image from my workshop on Playwriting and Politics: paid for by aspiring writers)

This blog was originally published in Autumn 2015.

On the Playwriting UK Facebook group there’s been a recent debate about paying for script feedback. I’ve followed it with interest, as one of five or six other individuals and organisations who occasionally post their professional services on this forum.

I’m writing this as an extension of the debate too, and am very interested to know what people think about the bigger issues of proper payment in the arts and paying to develop yourself and your work, so please do comment below: but I wanted to offer some context from the other side first.

There’s been some brilliant advice in the thread about how to get as much feedback as you can without spending money: joining writers’ groups, hearing friends read it out, submitting it to those sadly fewer and fewer theatres and writers’ organisations that receive unsolicited material and offer a script report to all, finding a way to doggedly push through and produce the play yourself so you can understand your work in three (rather than one flat) dimension – fantastic stuff. All advice I’ve also taken, and given, to other writers.

Now, maybe I’ve just been lucky enough never to be on the receiving end of really poor feedback that I’ve paid for (as in poorly constructed and poorly justified), but what’s actually inspired this blog is some of the language flying around in the discussion: particularly the implications regarding what happens when one starts paying for feedback, and what might lie behind some of us freelancers advertising the business of supporting playwrights.

We’re scammers.

You can’t trust us.

We don’t know how to give practical advice, only how to point things out.

And – astonishingly to me – we really won’t give brutally honest feedback anyway, because we want the writer to come back and part with their money for another draft later down the line.

That last one is actually suggesting that at the heart of what we do, we’re dishonest.

I think it piqued me more because it’s part of that bigger debate about people in the arts getting paid for what they do, and the automatic negative value judgements that arrive as soon as money comes into the frame.

There’s another comment that there are too many people trying to make money out of aspiring writers. I’d agree that maybe there’s too many, yes: it’s an overcrowded market – but that goes for playwrights as well as dramaturgs and script services. Also yes, some competitions don’t seem to understand that in gathering the work that creates their festivals, those who generate it maybe shouldn’t be paying over the odds for the privilege.

Do I make money out of aspiring playwrights? Yes.

So does the Arvon Foundation. So does Stephen Jeffreys. So does the workshop programme at Soho Theatre (yes, some are free but not all). It’s part of their income stream and you’ll find the numbers in the budget.

We tend not to question these big players. However when you’re freelance and not carrying the badge of a big established venue, in spite of your credentials, the assumption is often that you’re exploitative if you’re asking for money from playwrights.

I know that helpful feedback is not the preserve of the ‘trained’. That’s like saying only artists can ever have an opinion about art. I’ll be the first to admit that my wife is the first person to read all of my scripts, because she can sniff out writerly bullshit a mile off.

But her bullshit-sniffing qualities can’t really tell me what to do about it, or how, or technically why it might be the case that the script smells that way. Fortunately, I’ve got a bit of a march on now with my work and process, and can undertake that questioning myself. But other writers may not. I’ve worked with plenty of writers (a couple in the past week) who’ve said to me ‘the script report I got from this theatre said this, but I don’t understand why or what to do about it.’

This is why I don’t openly offer the writing of script reports anymore as a sole form of writer engagement, and strongly favour one-to-one discussion: and before you ask, it takes me the same amount of time to do both, so is nothing to do with gaining profitable hours and everything to do with creating something I believe is more useful for the writer.

I know a script report won’t tell you everything, and can certainly never solve everything. That it might tell you things you already know, or worse, tell you things you don’t know, but not what to do about them. Or can tell you things in such a convoluted or confused way that you don’t even understand it. That can (but shouldn’t) happen, of course. A very good script report can be absolutely worth its weight in gold – clear, concise, focused, practical.

That all said, there’s still just a strange tone floating around in the thread sort of suggesting that parting for money by asking a professional to engage with you over your work is the worst possible path you can take in your development as a playwright.

Again, this may just be me lucking out, but the most significant development I’ve ever had in my own career as a playwright has been from people who were getting paid to give it to me: as directors, performers, designers, literary managers, dramaturgs, creative producers, freelance or staff, and – further back – as lecturers and practitioner-tutors at university. I don’t think that’s necessarily an accident.

Anyway, having your integrity questioned is a bit of an occupational hazard as a dramaturg. At 23, when I’d already been working as the Literary Assistant at Soho Theatre for a year or so, the brilliant but formidable director Annie Castledine shot me down in a forum about dramaturgy to exclaim that I couldn’t possibly know what I was talking about yet.

She’s right that I didn’t know everything – but then neither did she – and also youth shouldn’t necessarily be a barrier to one’s understanding of how to support a writer. It’s not like they were letting me loose on commissions, but I was making a pretty good job of supporting the young writers’ group members and they seemed to agree.

I recalled this moment almost immediately when I came across the Facebook thread.

I want to talk about integrity (and in turn perhaps outline my own assumptions about the aims of those others who offer these services), but also to talk about the practice of writing script reports and why I don’t do it much anymore.

Most importantly though, I want to communicate the fact that I bloody love getting my teeth into working on the mechanics of a play, and a little bit about why that runs so deep in me.

In my second year at university a new module appeared called ‘Dramaturgy’. This was 1999 and most of us were intrigued by the promise of the subject to provide us with a better understanding of how plays worked.

It was slap-bang in the middle of the In-Yer-Face period: Sarah Kane was still alive, Mark Ravenhill and Anthony Neilson were creating plays pushing at the boundaries of taste and politics, British theatre was about to receive its biggest uplift ever via the Boyden Report, and interest in new plays – as well as how to nurture, sustain and develop the increasing number of new voices coming to the fore – was on the up.

In retrospect we were a bit of a guinea pig year for the module, but at the core of it were two solid practical tasks. The first was adaptation from prose – learning how to make a script work for theatre by building on strong choices from another writer in a different medium. This basically relieved the pressure on us to ‘have an amazing idea’, and allowed us to focus clearly on the requirements of the live medium and how to show, rather than narrate, the action.

This was what we were assessed on in fact – illustrating how well we had understood the nature of theatrical storytelling through making effective dramaturgical choices. My first draft tanked massively and was grossly (if enthusiastically) overwritten, relying too much on emotive surface dialogue rather than underlying actions and objectives: my first big learning curve.

Our second practical task was to research a given genre of theatre – not necessarily led by playwriting – and then pitch a bespoke season that could best represent that genre, and its defining characteristics, to a producing theatre. Our two lecturers took on roles as artistic director and executive producer, and took us firmly to task once we’d given our presentations.

I opted for Contemporary Women Playwrights, to which the initial reaction was ‘you can’t choose that, you’re not a woman.’ This was from one of the lecturers. So like a red rag to a bull, I insisted.

In the next two weeks I read forty plays by women, beginning chronologically with Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey (1958) and finishing up with Sarah Kane’s Crave (1998).

I made notes fastidiously. I absorbed structures, characters, worlds, stagings, theatrical languages, different forms of notation, attitudes, politics, cultures and perspectives, trying to knit it all together into a collective understanding.

At the end I came to a conclusion that still fascinates me now – all of these plays worked, but all of them were unique in their combination of elements: their dramaturgies. Sure, there were similarities, patterns, motifs and structures, but each writer employed them in their own particular way. They’d all created their own maps for the writing of their stories.

I wanted to tease them apart, cut through them like a geologist studying the strata of a rock formation, lay out all the parts like I was doing bike maintenance so I could understand how everything worked individually and therefore comprehend better the whole machine of a play. It switched me on. I wanted to work it out.

I wanted to be a dramaturg.

I wanted to be a dramaturg because I loved scripts, and I loved the people who seemed to be creating them.

I’ve been one for thirteen years now, and I still want to be a dramaturg because every new play is a fresh challenge. I love working with writers. I won’t bore you with a lengthy justification of professional experience here, because you can just click here for that if you want. All I’m saying is believe me, I want to work with writers so that they can create their strongest work.

I also happen to be one. I know how it feels from that side of the writing too and how desperate and confusing and muddling it can be. It just also happens to be that this side, from which I’m writing now, is also part of how I make a living to support my children and pay my way in life.

I promised I’d talk about the script report side of things purely practically: so, in brief, my approach to plays is always from the inside out – never to look at a play and expect it to work in a particular way before I’ve begun reading it. Not to assume I know finally what a play is, until the play has attempted to speak with me. To try and understand it from its own point of view, from what the writer is trying to achieve. To try to learn the play’s language first, and let it speak to me: otherwise I’m like a crass British tourist abroad shouting loudly in the face of a bewildered native speaker ‘I said THREE ACTS… THREE. ACTS.’

It would take a much longer article (and indeed, books have been written) to go deeper into what practical dramaturgy is with writers, but at the heart of it for me is conversation and the need for our vocabularies in talking about plays to stretch and evolve.

The other reason this Facebook thread caught my eye is that I’m halfway through delivering my first set of Playpens sessions: dramaturgical support that writers are paying for.

First of all via email, they respond to ten questions constructed to engage them consciously with the craft and intentions of their work.

I read the play, annotate, make notes – and only after this, look at their responses to the questions. I use them to guide me through my second read of the play, comparing writer intention to dramaturg’s interpretation: then we have our 90min – 2-hour conversation about the play on Skype or phone.

The breadth of vocabulary and reference points across these writers has been huge. For one, it was his first and only play, and his first ever professional feedback session. Words and phrases like exposition, cause-and-effect and subtext needed defining.

For others, it’s their third or fourth piece of work – and they’ve heard it read, been through the mill of feedback, and still can’t see the wood for the trees – these have been very different conversations.

Across them all, I’ve said things that have been met with ‘how?’ or ‘what do you mean exactly?’, being made to articulate my feedback more precisely and also sometimes – hold your breath – changing my mind once we’ve got under the belly of the play a bit. For the writer, I can’t see how a script report could create the same dynamic.

I’m often asked what the difference is between directors and dramaturgs. There are loads of brilliant new writing directors out there, and if you get one, you probably don’t need a dramaturg. But what I’ve noticed is that dramaturgs are great dramaturgs of a writer’s process, not just their play. We tend to try and help with the bigger picture too, how writers work, not just identifying problems in a particular script. It’s always the most rewarding work of all when a writer is led to unlock a stumbling block in their process – that’s progress that impacts far beyond one particular script.

I love playwrights. I love dramaturgy. I love how theatre, and writing, and therefore my role, is always gradually shifting and being challenged in new ways. It’s my job, and I’ve trained for it, and I’m bloody good at it.

There are always ways you can develop your work for free, and sometimes of course, the timing is much more preferable just for the word of an honest friend – early work, too raw to share in the industry may be best encouraged by trusted eyes. So if you can find them, and if they’re truly rewarding to your writing, please go for it.

And if you like, you can also argue (rather like my brilliant wife) that all of the above also smells a bit bull-shitty too. That’s your inalienable right.

But if it doesn’t, maybe give a go to those professionals who happen to make a living from it too. They’re out there, and I think when they say they’re ‘looking forward to reading your work’, they really mean it.

These individuals and organisations who offer script or writer development for a fee are not affiliated to this article in any way, but I thought it would be unfair not to mention them: