These conversations took place in response to an invitation from Kaleider in Exeter to take part in their Kallisions Artist Development programme. As a total technology and digital theatre novice (and long-time cynic), I wanted to learn more about this world that forms a large part of many writers’ work, so set up a few conversations to try and find out more.

Rik Lander is a writer and director of interactive narratives. He started out as a video artists in the 1980s as half of the Duvet Brothers. From experimenting in form by literally hacking up the material he moved into non-linear story telling through new media. He made magic-tree, one of the UK’s first web dramas, which went online in 2001. He produced, directed and script edited Wannabes, the BBC’s first interactive soap. Through his company, You Are Here, Rik acts as a consultant for people who want to use social or participatory media to tell stories. He does frequent public appearances and runs courses in several facets of multi-platform production, including some ground breaking short courses at the NFTS in Feb and March 2010. He was also the creator of The Memory Dealer which featured in Mayfest 2013 in Bristol.

Tell me a little about how you got into working with storytelling and technology.

I started out as an engineer – an electronics engineer for television, doing a lot of work around the editing suite – but at the same time I was making my own work and very successful in the 1980s making scratch video: taking footage and reediting it, and therefore changing its meaning – so some of it was very political. Some of it was just aesthetic experiments with form, trying to break the image, trying to make it do different things and so on…I toured a live multiscreen show with a big stack of televisions that would play multiple VHS: there were twenty-one sets so they could play twenty-one of the same image, or fourteen and seven, or seven and seven and seven. We’d edit those images so you could focus on a single screen, or make it a big pulsing image, that king of thing.

We did some very abstract stuff and some very narrative stuff. Then I saw my first video installation, and that inspired me a lot. I’d started to do these experiments in multiscreen narrative formats, where you take a single narrative and have three angles of perspective on the same scene, for example. It was playing with narrative in a three-dimensional space.

Harry, Duvet Brothers, 1986, multiscreen

Scratch was basically about deconstructing storytelling: taking a piece out, moving it somewhere else, changing its meaning or unearthing its hidden meaning. Like with the miner’s strike – we saw the strikers every day on TV and saw them confronting the police, but we knew that wasn’t the only side of the story, it had just been edited a particular way.

Blue Monday, Duvet Brothers, 1984

So I thought – the problem with this is passivity: an audience sitting there, watching the screens, getting the story exploded and stimulating their minds, but not getting hugely involved. With the installation work I wanted to change that.

The first piece I did had fourteen TVs and projection and sound and sets, and you basically went into three zones. It had a three-act structure I suppose, and each zone told you a different part of the story. It was all addressed at you, and effectively you were the person in the story. It got quite oppressive, large scale…so that was a combination of the original editing process and then adding in the narrative installation side of things.

Trial By Media, Rik Lander, 1989, installation

I carried on making that work and then at some point – I guess in the 90s – I discovered interactive media, and that was CD ROM: the available format before the internet and quite easy to programme. I made a documentary on that and then arrived at the internet and created a drama in which you as the audience member – the player of the experience – were central to the story.

But that was about creating a parallel between a character’s experience and your experience: you’d think you had free will but actually there was a lot of replication…she clicks on this link so you click on this link; she goes to this website so you go to this website, and so on. It was a play on what the internet was all about really – is it a place where you’re free or a place where you’re steered?

Having done that, I was then seen as an ‘interactive storyteller’ and was invited by the BBC to make one of their first web-based dramas. That was online for teenage girls, and came out in 2006.

How was the invitation to that framed? Was it written for a known audience of registered users to a particular website, or advertised widely…how did the audience arrive at it?

It was a mixed success, let’s put it that way! The BBC is a very strange organisation but fundamentally what they realised in the mid-2000s was that this young audience – particularly women – were using technology in a totally new social way: they would come home, immediately go online…a new phenomenon, not shopping but using chat-rooms or instant messaging – this was all a great revelation to the BBC I think! And their fear was that there was a danger of losing them because all they made was TV and radio. They did have the world’s biggest website, webpages for everything, but it wasn’t necessarily serving people in the way they wanted to be served. So we aimed to create a drama that would emulate the idea of communication and friendship, which was the basis of the online relationships they were conducting.

Wannabes, BBC, 2006, web drama

So we created this friendship rating – it was a Hollyoaks sort of thing – and every now and again they’d turn to camera and say ‘should I do this or should I do that?’ and the audience had to choose. In making a choice, for example, a crass one might be ‘shall I sleep with my best friend’s boyfriend?’ if you said yes your rating with the girl went down, but your rating with the boy went up. And vice versa if not.

And with seven characters in the drama, all with different ratings according to your choices, it meant that if your rating hit a certain level it would release unique material: only you could ever arrive at a particular score. But it also remembered all the choices you’d made, so could build quite sophisticated responses – noticing that you’re consistent, or erratic in your choices. All triggered by a database.

So was the whole series self-contained and pre-programmed, or did you have to create new material all the time?

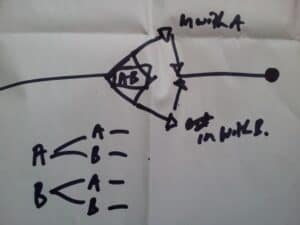

Fundamentally it was a linear drama – you could make choice A or B, for example – taking you on different paths, but they would always return to the same narrative spine, so you’d always end up with the same outcome, but having gone on a personalised journey with a particular relationship with the characters at particular stages. We call this a diamond structure:

So they might be like ‘oh you’re my best friend I love you’ or ‘you’re a bitch, I hate you!’ – depending on the scores you’d amassed with your various choices – but every player would end up watching the same ultimate fixed narrative play out.

And this is all seven or eight years ago.

Yes. And in answer to your question about the audience, one of the problems was that each new controller came in and changed the name of the website – its identity – and said ‘let’s do some new online drama’ and nobody ever looked back down the curve at what had been learned so the progression was a little slow.

This sort of choice structure you describe above – is this something you’ve applied to other work?

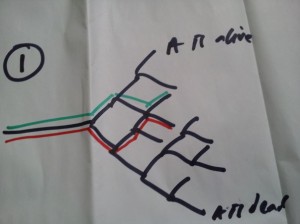

Yes. The other structure which gets highly problematic, but has been a common model, is the tree structure, where if you have a particular starting point for an interactive drama, and then an A or B branch to go down – at the end of each of the two branches there’s another A or B choice, and so on, so on…

…you have to make so much material, but one person only ever takes one route through it so in terms of time, it’s hugely inefficient. And it ends up with huge convolutions if you’re not careful – over here (green line), character X is dead, and over here (red line), they’re alive! It’s not always going to work.

But if you have a lot of different users presumably it’s not a waste, because lots of different journeys could be taken?

Well it’s a valid point, but – how much are they going to take different paths and how much are they going to make the same choice? If the choice is trivial it could be 50/50 but if it’s important – should I sleep with my best friend’s brother? – then more often than not you’ll make the choice that results in the narrative sparks flying, not the sensible moral thing. Unless you can incentivise them to do something different of course. It’s a problematic model…

…but in terms of exercising options and choices for characters – for character development – it’s quite a useful diagrammatic way of exploring dramatic potential…

…well it’s like life isn’t it? Your birth starts here, and then you go on to choice A or B, and A or B again and so on…but in life you can never go back.

[N.B. unless you’re writing a play like Gill Kirk’s innovative QM – see an interview with her here]

This is effectively the starting point that everyone takes, and then you hit the buffers of resources – all those choices take time to map out, think about, plot…and I’m not really convinced anymore that giving people choices – just choices – is really what they want anyway.

If you look at the Aristotelian model of storytelling, beginning middle end, highly authored, we know about that, we love it – then if you look at Augusto Boal then that’s absolutely about choice, intervention, empowerment for the audience – there’s two potential models there.

But audiences aren’t going to be conscious of those models at the point of engagement. They know they love watching Homeland or whatever, they don’t want to interact with it. And if you give them the choice to, they’re very quick at working out what’s good and bad about it. They’ll drop off and lose interest instantly when they’re realise they’ve no actual power in the story. Also they’ll double back – so, if I was playing on that diamond system of choice above, and didn’t like where I was going, I’ll go back and start again. Very often the first thing games players will do in terms of narrative is find the outer boundaries – so you might think ‘ah, I’ve got a structure where the inevitable conclusion is here’ – but they’ll search for all the other alternatives too.

Let’s put that aside though. With this [see image numbered ‘1’ above] what it allows you to do is keep your Aristotelian ‘quality control’ over the narrative – your auteur’s vision of the place you want to take them – but build in a genuine form of interactivity which is their relationship with the characters, and that’s actually a really exciting thing. And it doesn’t even have to be relationships with characters, it could be something else: but essentially that scoring system, where your choices go into a database, allows a learning experience to take place and be reflected back at you, the user.

These things feel more like the areas in which storyteller Hazel [Grian] works, where there’s this peripheral narrative going on in relation to a known, core narrative – you can develop personal relationships, other stories, your own pathways, but always a central spine to return to.

I love Hazel’s work and alternate reality games (ARGs). I use ideas from ARG in my own work, but creating a whole alternative world can cause problems. Basically…if you’re watching – say Homeland, right? You’re in the story and you’re in the moment, and you want to know what choice Brody is about to make, and a little pop-up comes up saying ‘find out what Brody was like at school’ you can go into it, that’s great, but also what you’re doing essentially is wandering off, away from the path which is plotting out ‘Oh My God Will Brody Live To See Another Day!’ which is why you give a shit about the story in the first place, where your emotional connection is.

So when you offer interactive stuff, it’s got to be essential in the first place, right in there, in the centre of the story, and giving peripheral stuff like ‘see this character’s medical records’, you’re like – I know she’s mad, I don’t care why, oh it’s very clever that you’ve mocked up some medical records – I don’t actually care unless it’s a clue to something totally revelatory and unknown: ‘oh, she’s actually got a diagnosed condition she’s told nobody about’ – now that completely changes how we read the story emotionally.

There’s a real danger in a lot of ARGs that what you’re encountering is totally peripheral. The danger is that it’s really good fun to make – you think ‘ooh I’ll make a nice fake website’ – but it’s not essential. The key is to keep interactivity essential to our emotional engagement with the narrative.

Moving on… there was this piece I made called Room 11 where you go one-by-one into a room where something’s happened – a hotel room, with the bed all skewed at an impossible angle – when you go in a light is triggered, there’s the sound of flies buzzing, when you look under the bed there’s a load of scissors and the pictures are whispering, and then there’s a monitor under the bed and as you lie down to watch the clip, it looks like a film of you, lying under the bed, whilst a woman explores the room…and a soundtrack kicks in of a couple – their answerphone messages, and the man is saying how amazing the room looks, the towels like a gentle kiss of a beautiful woman or whatever – but you know they’re disgusting, cracked, dirty – and what you start do is piece together a story.

Some people assume somebody has died in the room and then, eventually, you realise that you are the body on the floor under the bed, she’s the bereaved partner…so the idea then is that you’re active. You could just tell the story and it would be a passive exploratory construction – but the step I want to take is put the audience member into the story, take it that one little step further.

So that brings us up to The Memory Dealer in Mayfest 2013…

– where I put everything in! The whole lot – actors, interaction, ARG, mobile phones, installations – it was a huge experiment really. I wanted to something like The Bourne Trilogy really, or The Matrix, where there’s this hugely complicated narrative which is stretching out over several films, layer upon layer of philosophy. Can you do that in a pervasive performance, or is it just atmosphere? I wanted to make it a quite complicated story, to see what level people could take in. Hopefully we’ll do another one, but make it less complicated in form for certain.

The Memory Dealer, Rik Lander, 2010/13, pervasive drama

What do you feel you’ve learned from that experiment?

I would say that I would divide out the installations from the piece – the hotel room, the car, the tent, that kind of stuff – and the actor encounters, and make them two separate forms. Keep the spaces, but improve the quality of the live encounters within them instead. That’s my main choice.

That’s quite a distinct separation. What’s led to that conclusion?

Two reasons. One is that I’ve been learning from game-makers. My background is effectively linear video, broken-up to become interactive – and storytelling, so it’s all about narrative. Game-players have narrative built in to their experiences, but it’s not necessarily at the forefront: what they’re about is rules, and learning behaviours, so…in a game you discover that when you press this, and that, and twiddle that thing…I can jump over the gorge and get the gold, or weapon or whatever.

I think the problem with The Memory Dealer was that you never got round to learning the rules. Each space it changed – what do I do when I meet a performer? What do I do in the hotel? What do I do when I get in the car? How do I make the installation work for me? Everything had different rules, so I would go back and make it much simpler. “Listen very carefully to what is being said in your head. Try and absorb and respond. And when you meet someone, follow their advice.” That could be it.

The other thing – I mean I love this installation form – but if we’re going to do these complicated stories, then meeting characters to communicate exposition is much more direct and clean. Installations are much more about atmospheres, mystery, piecing things together – we need more directness.

When you work, how far are you adapting a completed prose narrative in your head, and how far is the form instructing the direction of the narrative? Do you ever find yourself making big narrative shifts in the early stages because the technology can deliver a more effective story outcome?

Um…I’m not sure…

There is an assumption in my question there about how you work though…

Yes and it’s completely wrong! I think…before I start – you can do what you like! – but before I start, I ask ‘why the hell am I making an interactive drama?’. Why not just make a play, or write a short story or a film? That has to be the primary…I have to be upfront about that. So then the question is ‘how is this interactive? What does that add?’ and for me that’s about audience agency.

So…in what way do I give the audience some control over what the outcome is, over what happens…I don’t think I’m really using the technology to direct narrative outcome, I’m using it because it helps me logistically. My interactivity is either psychological or physical, in a sense.

What other projects are you wanting to do now?

I’m kind of tempted to do something in a theatre actually.

How radical is that!?

I know! I would like to try and do an interactive play in a theatre. I’ve got a piece in mind, very early days though.

What’s leading you to a theatre space though?

A few things. I suppose one is credibility in a sense, in that, for me – The Memory Dealer came out of interactive drama – but not theatre in a ‘respectable’ way I suppose.

That’s about audiences too I suppose, about how they choose to accept or reject material depending on how the context labels it. I know I’d have a slightly different criterion for acceptance depending on whether I was roaming around the streets or being in the Bristol Old Vic or somewhere.

I think because I’ve been doing pervasive drama, which is all about coming out of the darkened room, I now want to go back into the darkened room and ask ‘can we take what we’ve learned out here, and apply it in there?’. If it does work then – cool – we can sell tickets in a more conventional way and possibly reach new audiences too.

Is it the technology that you see being tried out in that darkened room, or the structures that technology has given you – choice, outcome, pathway, interactivity…?

Um…

I may be being too binary about this: as I come into this world of the digital I see it as one thing over there, with theatre over here – but actually there’s elements that are dragged across into one another: it’s about what’s useful when.

Yes, I don’t think you should look at this technology any differently to how you look at set or costume or lighting or make-up. You say ‘for this production of Macbeth I need to have…’ and you don’t…I mean it’s normal isn’t it, to bring in what you need? But it does inform how you write it, the knowledge that it’s out there and available to use.

It’s really about knowing the list of platforms for communication: so you’ve got…audio, subtle-mobs, sets that play sound, SMS, phone calls, QR codes, NFC (like Oyster cards, triggering something to happen), sensors, installations, radio transmissions, GPS apps and triggers, getting video or maps delivered to your phone…a lot of this stuff you can do on the AppFurnace platform. You could make an app now, make it in an hour, take it off and test it.

Sound is very evocative, great for writing, because you have that direct control over experience. Download it and off you go, transported to another world by the writer’s words. The trouble with contact technology – QR codes and so on – is that the action can take you out of the story quite quickly, it’s somewhat alienating. When you get an SMS from a fictional character you can suspend your disbelief and get that it’s from somebody: but with a QR code it’s artificial, it’s programmed – you know it’s not real.

That’s a useful list to be chewing on! Thanks Rik – that’s great.

You’ll have fun. Enjoy it!

Rik followed up with some other links, many of which are embedded above. You can also follow his blog, look at his website and see documentation of various artworks here.